When Technology Meets Humanity: Harnessing New and Emerging Technologies at the End of Conflict

New and emerging technologies offer significant contributions toward facilitating the end of conflict and protecting and easing the effects of conflict on the civilian population. Over the past decade and more, security and legal scholars have devoted enormous attention to the role of new technologies in targeting and surveillance, including GPS-guided weapons, battle networks, collateral damage estimation methodology (CDEM), cyber, drones, and autonomous weapons. In contrast to this focus on the use and effects of such capabilities in the conduct of hostilities, however, the potential for emerging technologies to enhance humanitarian and security objectives at the end of conflict—just as they already do effectively in disaster management and relief—has received little to no attention.

For several years, our End of War Project explored and highlighted the role that new and emerging technologies can play as protective and cooperative tools as conflicts end or begin to end. Based on academic research and multi-stakeholder consultations with legal, security, and humanitarian experts, the End of War Project’s white paper, titled “When Technology Meets Humanity: Shifting Policy Towards Protection in Conflict,” advocates for harnessing new and emerging technologies to promote humanitarian values at the end of conflict. Drawing attention to a scholarly and policy gap related to the use of technology at the end of war, the white paper provides real-life illustrations (such as how technology has been used to limit human trafficking or enhance the protection of humanitarian actors) and recommendations to drive a policy shift and encourage the development and deployment of new technologies for protective purposes during and at the end of conflict.

The End of War as a Concept

The end of war is both a temporal and a substantive concept. As a temporal matter, the end of war refers to the spectrum of time from the winding down of conflict, through the formal or informal conclusion of fighting, to the early post-conflict phase. Substantively, the concept of the end of war includes a plethora of challenging policy, legal, and strategic issues, such as identification of the actual end of a conflict as a legal and factual matter, release and repatriation of detainees, accountability for international crimes, rebuilding of civilian infrastructure and capacity, humanitarian assistance for displaced and vulnerable populations, and much more. In particular, the end of war introduces significant uncertainty about the applicable law and the implementation of that law, including unique challenges driven by the uncertainty inherent in the complicated question of when a conflict actually comes to an end.

Some of the issues explored throughout the project and in the White Paper arise during conflict as well and are not exclusively limited to the end of war. This overlap does not detract from the white paper’s contribution. On the contrary, technology must be channeled towards more protective and humanitarian purposes both during and at the end of war.

Which Technologies and for What Purposes?

Recognizing the speed at which emerging technologies evolve and the need to be constantly attentive to ethical or legal concerns, several emerging technologies are of particular relevance:

– Machine learning tools to aid assessment and decision-making. Machine learning tools can help process volumes of data from a variety of sources, fuse information, and identify patterns that may not be obvious to humans. These tools can help provide additional context and insight to inform human decision-making.

– Machine learning tools to optimize functions. Machine learning can also be used to solve specific complex problems, such as supply chain management or resource allocation. One example would be speeding up the delivery of foodstuffs and medical supplies in war-torn areas.

– Blockchain. A blockchain is a distributed approach to securing transactions using computing power and exchanges between trusted participants, creating a secure, shared, and immutable tool for recordkeeping between and among disparate entities. Within alliances but also between warring parties, blockchain minimizes misinformation, increases trust, and guarantees the validity and security of the information shared.

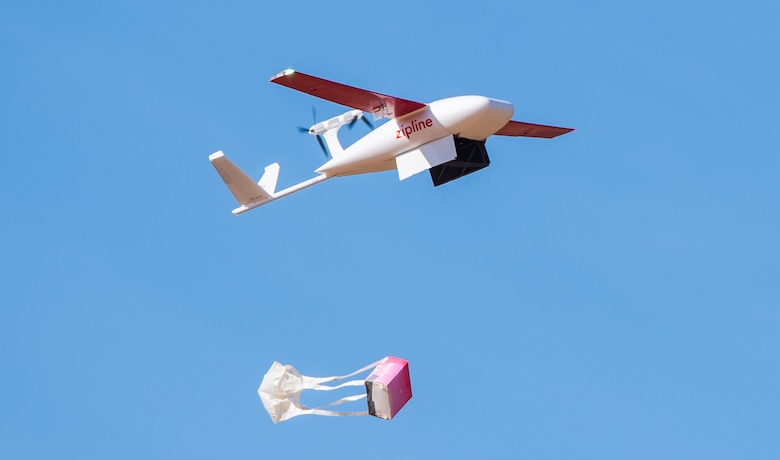

– Autonomous systems and remotely piloted vehicles. Pilotless vehicles can provide capabilities such as surveillance or logistics with greater persistence and without risk to human operators. Remotely piloted air, land, or sea vehicles can access areas where communication is limited, personnel for the platforms is unavailable, or affected communities have become isolated. Drones can be used to deliver medical supplies to populations affected by conflict or even blood to wounded people, as already tested in Rwanda.

– Biometrics. Biometrics can be a powerful tool for providing humanitarian aid, with appropriate attention to and safeguards regarding data security and human rights. Fingerprints, DNA, or retinal scans can be employed for registering displaced persons and finding more efficient ways to tailor and deliver assistance. Facial recognition may be used to identify victims, help families unite in the wake of the conflict, and enhance medical treatment by allowing medical teams to quickly access medical records.

– Satellite imagery. Satellite imagery can be used to collect information about the location of atrocities and the commission of war crimes. This technology holds unique promise in the field of accountability, allowing the verification of facts, even long after the conflict has ended. Satellite imagery may also effectively document troop movement and damage to cities.

Although by no means exhaustive, this list shows that technology can be used to tend to affected populations and stabilize the security environment across the spectrum of ending conflict, from preparing and then facilitating the end of conflict to supporting the restoration of peace.

The roundtable and workshop discussions emphasized repeatedly that any development and use of technology must be matched to the needs of the population, decision-makers, and other actors involved in this stage of conflict. This match between on-the-ground needs and technology is the key to adaptability, accessibility, and, ultimately, effectiveness. Further work in the policy and scholarly space must focus on: 1) understanding the range of challenges that civilians, warring parties, humanitarian organizations, and other actors face; and 2) exploring the possible uses of technology to address those needs and gaps to “match” problems and opportunities.

Opportunities for New and Emerging Technologies to Contribute at the End of Conflict

Facilitating the End of Conflict

New and emerging technologies can play an important role in minimizing uncertainty at the end of conflict, which can be an obstacle to peace. Such uncertainty could relate to whether the strategic picture allows for negotiation or other action to try to end the war or whether the adversary is abiding by negotiated ceasefires and other agreements. Autonomous systems, drones, and satellite imagery can gather credible information on damage in conflict areas and the movements of fighters and civilians, creating an accurate picture for decision-makers, and machine learning tools can then analyze such data, potentially even in combination with data gathered from other sources.

More important, in many cases, ending a conflict means avoiding escalation. Warring parties often cause more violence as they seek to gain an advantageous posture for ending the war or respond to actual or perceived atrocities or violations of commitments. Imagine technological tools that could enable the parties to verify and trust information about the position of forces, the adherence to ceasefires, or the demobilization of forces, such as blockchain and other means of securing information flows. Mitigating uncertainty and enhancing trust and verification can help smooth the path to peace by removing common obstacles and sources of re-escalation.

Other opportunities include facilitating a more orderly and resilient demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration (DDR) process through tracking of disarmament and more targeted reintegration by region, sector, and skill set. Organizations and government agencies can provide remote psychological first aid for former combatants and civilians. Algorithms can predict refugee paths based on patterns and weather, allowing relief organizations to be proactive rather than reactive, anticipate crossings and other mass movements, and better allocate resources accordingly. Technology enabling better mapping of conflict areas can then help organizations tailor relief efforts to different needs and vulnerabilities.

Sharing and Safeguarding Data and Information

Facilitating the sharing and safeguarding of information can improve the ability of former adversaries to maintain a tenuous peace after hostilities cease.

Throughout the end of conflict space, data and information are of critical importance to identify the needs of vulnerable populations, manage the flow and security of information during negotiations, and track the return of displaced populations. Trust in the validity and secure use of information is a consistent concern for the many actors involved or affected.

Different stakeholders have different needs for information, levels of willingness to share information, and relationships to the individuals or communities whose information they collect and use. For example, humanitarian organizations produce enormous amounts of information, but often lack the in-house capacity to analyze and process it. Militaries and governments naturally are reluctant to share information, and international organizations have their own imperatives and limitations with respect to the data they gather and use. The law applicable to the data might also change if and when such data is transferred to a foreign actor. Blockchain and other developing tools offer numerous opportunities for secure shared information and communications platforms, such as tracking donations and ensuring that aid earmarked for a certain purpose or recipient gets delivered accordingly.

New technologies that predict and assess the flow of displaced people and refugees can contribute to more efficient and supportive programs. Technologies adapted quickly in the rush of assistance to civilians fleeing Ukraine, for example, helped to enhance safety and security in the support of refugees at a highly uncertain time.

Knowing the number, medical condition, linguistic needs, and other critical information of displaced communities is critical for the provision of supplies, housing, transportation, services, and other basic assistance. At the same time, however, that same information in the hands of a State or other actor can be extraordinarily dangerous. As one example, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has collected massive amounts of biometric data on Rohingya refugees who fled Myanmar into Bangladesh. Negotiations and arrangements for their return to Myanmar raise a substantial risk of that biometric data being transferred or otherwise falling into the hands of the Myanmar authorities. Refugees and displaced persons generally have no choice but to share their biometric and other data to receive services and assistance, but that data then makes them vulnerable if it lands in the wrong hands, so deploying technological tools to bolster data security is essential.

Other key issues include developing systems for interoperability in the information space, both among like organizations (humanitarian to humanitarian or State to State) and across sectors. Technology can help by building a shared vocabulary and lexicon, translations, and trust among actors working in the same space.

Enabling and Enhancing Humanitarian Action

Humanitarian organizations face extraordinary dangers operating in wartime and post-conflict environments, including the challenge of how to notify friendly forces of their location while protecting that location from discovery by hostile forces. Technology that enables encrypted notification and sharing of location will help to protect humanitarian workers and organizations and thus enhance their ability to help populations in need.

Humanitarian experts also expressed the need to communicate on safe, user-friendly platforms that verify the identity of actors and the information communicated. Blockchain, a decentralized database which stores a registry of assets and transactions across a peer-to-peer network, could answer such needs.

Data protection is another daunting task for humanitarian organizations, who have been “exposed to a growing wave of digital attacks and cyber espionage and have become highly prized targets.” In 2022, an unprecedented cyber-attack severely compromised data held by the International Committee of the Red Cross, highlighting the need to find solutions to protect the data of those who are most vulnerable, including those separated from their families due to conflict or disaster.

Accountability and Redress

The international criminal justice field is already deeply engaged in the use of new technological tools to assist with the gathering, storage, and processing of information about atrocities and other harms committed during armed conflict and other situations of violence. In Ukraine, for example, Bellingcat and other actors have set up networks for the sharing and receipt of photographs and videos of atrocities for future use by courts and tribunals. Satellite imagery and drones can be and are used to gather evidence, and new databases and repositories are being created in real-time to store information in a manner that can then be admissible in a court of law.

Humanitarian organizations are often first on the ground after devastation and conflict, bearing witness to the destruction caused and abuses committed. Registering evidence or testifying before a criminal tribunal is not in the mandate of such organizations, but tools can be developed to prevent the loss of that valuable information without compromising the posture of relief workers. Some have suggested the development of a common open-source questionnaire that organizations can use to collect information. A centralized database can also be used to input witness and victim statements, such as those in use by CaseMatrix or CaseMap.

However, criminal accountability is only one dimension requiring attention. Redress and reparation, which are critical steps in the post-conflict process, depend on information and reliable records to ensure that individuals can recover their assets or property. Unsecured means of collecting and storing such information can be susceptible to theft, scams, and other criminal mischief.

Equally problematic, most individuals fleeing from conflict do not have the time or the means to bring with them documentation of their birth, bank accounts, or property. Technology that stores such information in an encrypted manner can facilitate redress and restitution efforts, in addition to ensuring that displaced persons, asylum seekers, and refugees actually receive the assistance to which they are entitled.

Rebuilding and Reducing Vulnerability

During war, any and all tools to reduce vulnerability are essential. Civilians are vulnerable to attack and starvation, internment, disease, adverse weather, and many other hardships. Combatants captured by the adversary are also vulnerable, including to mistreatment, loss of rights and privileges, and disappearance.

Technology can mitigate the impact of conflict on vulnerable populations and the hardships that arise as conflicts come to an end in three main areas. First, satellite imagery and enhanced data processing capabilities can enable a more accurate assessment of the damage caused to civilian infrastructure, in real-time, and thus improve the quality of the humanitarian response and post-conflict rebuilding efforts. Second, artificial intelligence and facial recognition can assist with family reunification and the identification of the dead, such as in Ukraine, where access to large datasets containing billions of photos has been helpful. Third, technology can help predict and prepare for movements of population, manage the records of refugees and internally displaced persons, and administer humanitarian aid with greater transparency.

Any such use of technological tools raises the specter of misuse, exploitation, and violations of privacy. Systems to protect against such abuse are therefore critical, including safeguards in data collection and storage and built-in systems to report concerns and complaints. Emerging technologies must be approached with a sober recognition of the ethical and legal considerations that can arise and clear solutions for risk mitigation. The white paper deliberately takes the uncharted route of focusing on opportunities and advocating a problem-solving approach, to complement scholarly literature addressing accountability, data protection issues, and autonomous weapons.

Conclusion

The possibilities outlined here are only a few examples of how technology can contribute at the end of conflict. If technology is used successfully to alleviate the suffering of victims and forge the path to recovery in the wake of earthquakes and floods, could it be used for similar purposes as conflicts come to an end?

We hope that our research and recommendations can pave the way for more work on these important issues and spearhead a much-needed policy shift. Breaking the stigma that technology in war is solely about attacks and lethality can enable international organizations, humanitarian experts, militaries, tech companies, and scholars to work together to shape this new and promising humanitarian role.

***

Laurie R. Blank is Clinical Professor of Law and Director of the International Humanitarian Law Clinic at Emory University School of Law.

Daphné Richemond-Barak is Assistant Professor at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy, and Senior Researcher at the Institute for Counter-Terrorism at Reichman University.

Many thanks to our co-sponsors – the American Red Cross, the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, the Lieber Institute for Law and Land Warfare – and to the participants in the Fall 2020 Global Dialogue, the March and June 2022 roundtables and the September 2022 workshop.

Photo credit: Roksenhorn