Balloons and Drones? The Least of Our Worries Regarding China

“Let’s be clear – the PRC does not invest; they extract.”

General Laura J. Richardson

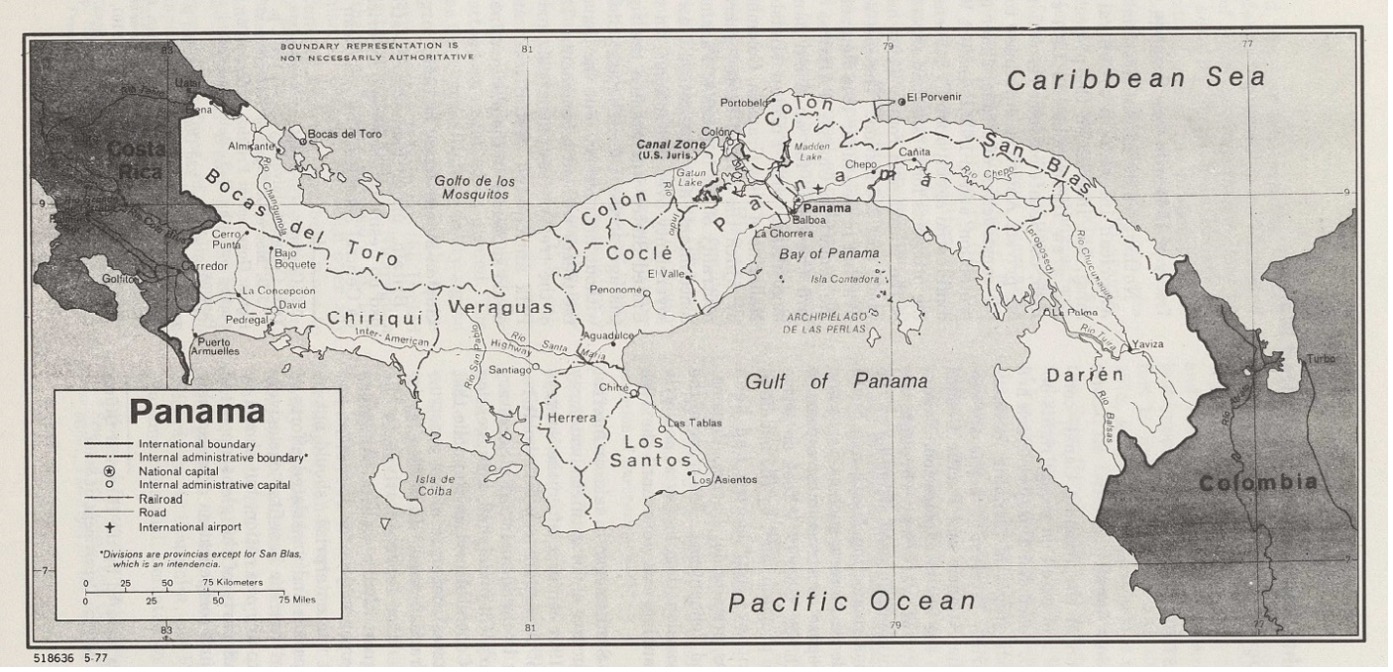

A map of Panama with the Canal Zone denoted as U.S. Jurisdiction.

A map of Panama with the Canal Zone denoted as U.S. Jurisdiction.

“The land divided, the world united.” That was the official motto of the Canal Zone, a U.S. territory that seemed to cease existing with the signing of the Panama Canal Treaties in 1977. This tiny strip of land and water on the Isthmus of Panama has enormous strategic importance and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) recognizes this. They are actively moving to control the entrances to the Panama Canal (the Canal) using State-owned enterprises and investing billions into Panama.

In fact, the PRC is essentially in a position now to: (1) use the Canal to surveil the United States’ movements, just as the United States used the Canal before the Second World War to surveil Japanese commercial and military assets; and (2) adopt a stratagem to block the Canal eliminating the United States’ ability to quickly move its own assets between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, just as the Japanese strategized mid-Second World War. The U.S. National Security Strategy of 2022 states that the PRC is our only “competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it.”

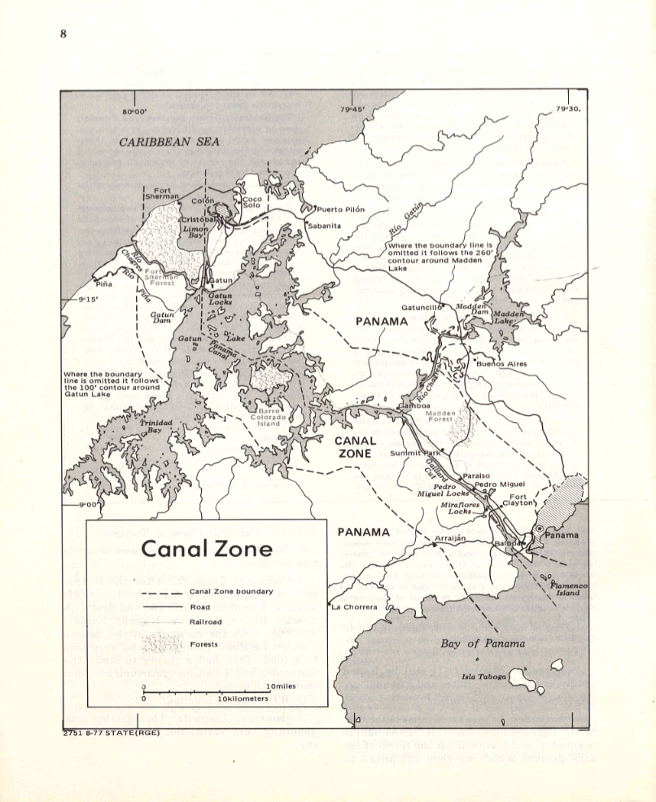

A map of the Canal Zone at the time of the Panama Canal Treaties of 1977.

A map of the Canal Zone at the time of the Panama Canal Treaties of 1977.

As such, balloons and drones are the least of our worries regarding the PRC. This post offers two courses of action the United States can employ to legally secure the canal ensuring this waterway remains open to its use.

Historical Context of the Canal and its Treaties

The Canal Zone motto is consistent with Article XVIII of the Hay-Bunau-Varrilla Treaty of 1903 (“Hay Treaty”) which stated, “[t]he Canal, when constructed, and the entrances thereto shall be neutral in perpetuity … .” That treaty was the initial treaty between the United States and the Republic of Panama, a newly established State as it was a province of the Republic of Colombia that the United States helped liberate. In fact, Article I of that treaty acknowledges as much stating that the “United States guarantees and will maintain the independence of the Republic of Panama.”

Article II provided that the newly established “Republic of Panama grant[ed] to the United States in perpetuity the use, occupation and control of a zone of land and land under water for the construction, maintenance, operation, sanitation, and protection of said Canal … .” This zone was to be

the width of ten miles extending to the distance of five miles on each side of the center line of the route of the Canal to be constructed; the said zone beginning in the Caribbean Sea, three marine miles from mean low water mark, and extending to and across the Isthmus of Panama into the Pacific Ocean to a distance of three marine miles from mean low water mark … .

Article XXIII reserved for the United States “the right, at all times and in its discretion, to use its police and its land and naval forces or to establish fortifications” should it “become necessary at any time to employ armed forces for the safety or protection of the Canal, or of the ships that make use of the same, or the railroads and auxiliary works … .” Nevertheless, why does this treaty matter when President Carter signed the Panama Canal Treaties purporting to supersede it?

President Carter’s Panama Canal Treaties of 1977

It matters because while the world was united by the canal, it is not so clear whether the treaties were. For clarification, there are two treaties: the Panama Canal Treaty (that terminated on 31 December 1999); and the Panama Canal Neutrality Treaty (that remains in effect). It is the second treaty, the Neutrality Treaty, that matters when considering whether Panama and the United States reached an agreement under the U.S. Constitution and international Law. The pivotal questions are: (1) whether there was a “meeting of the minds” when the Panama Canal Treaties were ratified; and (2) whether the Hay Treaty was properly “infringed and rescinded” by the legislature.

Whether There Was a “Meeting of the Minds”

According to Jefferson’s Manual and the Rules of the House of Representatives, “Treaties are legislative acts. A treaty is the law of the land. It differs from other laws only as it must have the consent of a foreign nation, being but a contract with respect to that nation.” Jefferson recognized that a treaty is a contract between two nations and a contract requires there to be a “meeting of the minds” between the two parties. Charles H. Breecher noted,

Here, I want to make it absolutely clear that if there is one thing that is beyond any argument in international law, it is that to ratify a bilateral—and again I stress bilateral treaty—the parties must agree in their instruments of ratification to the same written text. Otherwise, there is no meeting of the minds, as required for ratification.

While it is true that President Carter and General Omar Torrijos Herrera signed the Panama Canal Treaties, there were two versions of the Neutrality Treaty signed by both men. The U.S. Senate advised and consented to one version of the Neutrality Treaty that included the “DeConcini Reservation,” written by Senator Dennis DeConcini. This reservation stated, “… if the Canal is closed, or its operations are interfered with, the United States of America and the Republic of Panama shall each independently have the right to take such steps as each deems necessary, in accordance with its constitutional procedures, including the use of military force in the Republic of Panama, to reopen the Canal, as the case may be.”

This was unacceptable to the Panamanian leader and President Carter implies via his diary entry that he suggested he write his own reservation:

The fact is that the text of the treaty expresses our nonintervention commitment. This is repeated in the [Organization of American States] and UN charters, which we certainly would not renounce, and ultimately, if Torrijos wants to, he can issue a reservation about his understanding of what the treaties mean on intervention in the internal affairs of Panama. We all decided that it would not be good to try to amend the second treaty in order to accommodate a problem with the first treaty (emphasis added).

The Restatement of the Law (Third), The Foreign Relations Law of the United States, § 313 Comment f. stated

f. Reservations to bilateral agreements ... . If a reservation is attached at ratification, it constitutes in effect a rejection of the original tentative agreement and a counter-offer of a new agreement. The other party must accept the agreement as revised by the reservation; if its ratification process has already been completed it must be reopened to consider the reservation.

General Torrijos did then add reservations to the Spanish version of the Neutrality Treaty essentially nullifying the DeConcini Reservation. Specifically, the third reservation states, “[t]he Republic of Panama declares that its political independence, territorial integrity, and self-determination are guaranteed by the unshakeable will of the Panamanian people. Therefore, the Republic of Panama will reject, in unity and with decisiveness and firmness, any attempt by any country to intervene it its internal or external affairs.”

President Carter then signed Torrijos’s version without giving the Senate the opportunity to advise and consent. Section 314 Comment c. of the Restatement directed,

c. Reservations by other states. If another party formulates a reservation to a treaty to which the United States is a party, the reservation cannot become effective as to the United States, through acceptance or failure to object, unless the Senate has given its consent. In multilateral agreements, however, the Executive Branch has developed the practice of accepting or acquiescing in reservations by another state, entered after United States adherence to the treaty, without seeking Senate consent. Constitutionally, that practice must depend on an assumption that the Senate, aware of Executive practice and acquiescing in it, in giving consent to the treaty also tacitly gives its consent to later acceptance by the Executive of reservations by other states (emphasis added).

Reporter’s Note 2 of Section 314 elucidated that the Executive practice of not seeking consent from the Senate to reservations came about from President Carter’s administration taking the position that Torrijos’s counter-reservations were mere “understandings that did not change the United States interpretation.” According to Evans, “[N]onetheless, when Panama submitted its last minute counter-reservation nullifying U.S. rights, President Carter and his State Department failed to ask for ‘Advice and Consent’ on the ‘most substantive change in the text of the treaty that can be imagined’” (in his book, Evans also explains other issues related to the treaties). Thus, there was no meeting of the minds between the two countries and the Panama Canal Treaties were null and void.

Whether the Hay Treaty was Properly “Infringed and Rescinded” by the Legislature

According to Jefferson’s Manual and the Rules of the House of Representatives, “Treaties being declared, equally with the laws of the United States, to be the supreme law of the land, it is understood that an act of the legislature alone can declare them infringed and rescinded.” Article I of the Panama Canal Treaty purported to terminate and supersede all treaties between the United States and the Republic of Panama concerning the Panama Canal. It is true that the U.S. Senate gave advice and consent on the Panama Canal Treaties. However, Congress (the legislature) consists of both the Senate and the House of Representatives.

According to Evans “No ‘act of the legislature,’ i.e., an act agreed to by both Houses of the Congress, was involved because the House of Representatives did not participate. Thus, the abrogation was done by the President and the Senate in contravention of Jefferson’s Manual and the Constitution itself … .”

It is clear this is important because the Hay Treaty is still in effect granting sovereign control to the United States of the Canal and the zone around the Canal. In addition, Article XVIII prescribes that the canal and its entrances shall remain neutral in perpetuity. The entrances to the canal are the Ports of Balboa and Colon and currently are controlled by State-owned enterprises of the PRC.

The PRC’s Move on the Canal

The PRC’s move on the Canal has been slow and methodical beginning with “small footholds even before the withdrawal of US military forces in 1999.” It is the only member of the UN Security Council that has not signed the Panama Canal Neutrality Treaty. Commentators note, “Even Chairman Mao Zedong in 1964 rejected the US military presence and supported Panama’s struggles to regain sovereignty in the Panama Canal Zone. In that regard, and in 1973, Chairman Mao Zedong authorized China’s ambassador to the UN to reiterate Panama’s demands for US military withdrawal from the Panama Canal.”

Nevertheless, the PRC’s approach toward the Canal has gradually become more hands on and bold. As General Laura J. Richardson, former Commander, United States Southern Command, noted,

But in terms of the investment, China and the strategic investments that they make, you know, just like the Panama Canal, when you enter and exit and on either side you have Chinese State-owned enterprises. And what I worry about Chinese State-owned enterprises that have capability and infrastructure there is that they can be used for dual use, which means civilian but also military.

Rodriguez and Mohlin explain that,

Hutchison Whampoa, which is a Hong-Kong-based port operator company, established two corporate offices in Panama: the first known as Hutchison Ports in 1995 and the second called Panama Ports Company in 1996. This move led to China administering three important ports in the Panama Canal area of operation in 1997, one on each side of the Isthmus of Panama. The most important can be said to be Hutchison Ports PPC-Cristobal in the Caribbean Sea as it is also connected to the Cristobal Cruise Terminal, allowing China to have a firm hold over that side of the isthmus. The other port, Hutchison Ports PPC-Balboa, is on the Pacific seaside.

Since assuming command of U.S. Southern Command, General Richardson has iterated to Congress that PRC State-owned enterprises “are engaged in or bidding for several projects related to the Panama Canal, a global strategic checkpoint, including port operations on both ends of the canal, water management, and a logistics park.” In 2023 and 2024, she reiterated this sentiment in her written statements and testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

The PRC has additionally increased diplomatic relations with the Panamanian government and entered into bilateral agreements with Panama. Two of these bilateral agreements are of particular interest: the China-Panama Bilateral Agreement (CPBA) XXII; and CPBA XXXVI. Rodriguez and Mohlin explain that CPBA XXII dictates that the PRC and Panama give Most Favored Nation status to each other’s international commerce vessels “in terms of infrastructure, ports, customs, visa exceptions, payments, and logistics.”

Meanwhile, CPBA XXXVI “established that both countries shall collaborate in navigation aids training, seafarers training, investigation of maritime accidents, maritime documents, and protection of the maritime environment.” The PRC also had support from the Panamanian government to move its embassy into the old canal zone on Amador Causeway, but the Panamanian people protested. It can be presumed this was a strategic attempt to control an area where the United States previously had coastal artillery battery positions to defend the Canal.

Rodriguez and Mohlin note that “The risk is, of course, that Chinese control over the entry ports to the canal can lead to something akin to a naval blockade of the entire canal, but without the apparent use of military force.” General Richardson iterates this sentiment in her 2023 written statement to Congress: “[i]n any potential global conflict, the PRC could leverage strategic regional ports to restrict U.S. naval and commercial ship access.”

Two Courses of Action (COAs)

So, what is to be done to protect the Canal?

– COA 1: Declare that Panama has breached the terms of the Treaties by allowing PRC State-owned enterprises to control the Ports of Balboa and Colon, considering Chinese State-owned enterprises are dual use as civilian and military, and employ our right to defend the Canal against foreign attack as provided in the Neutrality Treaty by reestablishing complete control over the Canal and Zone.

– COA 2: Declare that the Panama Canal Treaties of 1977 are void, the Hay Treaty is still in effect and move to secure the Canal the United States built and the zone granted the United States in perpetuity by that treaty.

***

Captain Andrew Augustus Whitlock III currently serves as an administrative law and national security law attorney at U.S. Army North (Fifth Army) at JBSA Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

Photo credit: Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz