Strait Talk: Time to Exercise Navigational Freedoms in the Taiwan Strait Beyond Mere Transit?

conducted_a_Japan-U.S.-Australia_trilateral_Exercise_01.jpg)

Last month, a Japanese naval vessel traveled through the Taiwan Strait (the Strait), a first in the history of Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force, along with naval vessels from Australia and New Zealand (a first for New Zealand since 2017). A few weeks prior, two German naval vessels transited the Strait for the first time in two decades. Naval vessels from Canada and the United Kingdom occasionally pass through the Strait, while U.S. naval vessels and aircraft routinely transit the Strait on a near-monthly basis. Official statements usually describe the transits as just that, passing through the Strait simply to move between the South and East China Seas or en route other locations (see, e.g., here and here).

While these seemingly historic transits of the Strait are important exercises of some navigational freedoms, the international community should consider openly exercising other high seas freedoms of navigation in the Strait, in other words conducting other naval activities in the Strait beyond merely navigating through it for the limited purpose of moving from one ocean area to another.

Given the Strait is wider than 24 nautical miles, a relatively broad corridor—one that lies beyond and between the opposing twelve-nautical mile territorial seas (TTS) along the coasts of mainland China and Taiwan—runs through the entire Strait. That corridor overlaps with China’s and Taiwan’s contiguous zones (CZs) and exclusive economic zones (EEZs). (For shorthand, this post will refer to this corridor of water beyond TTS simply as “the corridor.”) Even so, under international law, no State may claim or exercise sovereignty over the corridor. Instead, the law guarantees the international community high seas freedoms of navigation and overflight, and other lawful uses of the seas related to these freedoms (hereinafter shorthanded as “navigational freedoms”), not simply a right of transit. Those navigational freedoms permit a range of other naval activities in the corridor, such as stopping and anchoring, collecting intelligence, launching and recovering aircraft, and conducting drills and exercises (see here, chapter 14). To the extent any of these is already being done, that is not apparent from the official statements or reporting on the transits noted at the outset of this post.

From a legal perspective, exercising other navigational freedoms in the corridor (i.e., those beyond merely transiting it) can help protect those freedoms from unlawful encroachment, particularly by China. Exercising other navigational freedoms also mitigates the risk that mere transit becomes normalized as a de facto or customary ceiling of acceptable use of the Strait’s corridor, despite international law permitting more. Indeed, that some view the recent transits of the Strait as historic or recent firsts—if not provocative and involving “disputed waters”—suggests reluctance on the international community’s part to transit the Strait at all, let alone conduct other permissible naval activities. This, in turn, contributes to a de facto encroachment on even the most basic navigational freedoms preserved to all States in the Strait’s corridor.

Although others have written about legal aspects of the Strait, this post takes the recent historic transits as an opportunity to explain the Strait’s status under international law of the sea, the international community’s navigational freedoms in it, and why States can and should consider exercising more of those freedoms.

Policy Risks & Benefits

There may, of course, be policy risks to conducting other naval activities that exercise navigational freedoms in the Strait beyond mere transit. China may view such activities as provocations and use them as a pretext to escalate its already coercive activities in and around the Strait.

Yet China has already intensified its coercive activities and will likely continue doing so regardless of what other States do in the Strait. Moreover, refraining from other navigational freedoms in the Strait, out of fear of escalation, allows China to essentially hold those freedoms of navigation hostage and supplant a longstanding balance between coastal State interests and the international community’s navigational freedoms in the seas. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), specifically its provisions concerning navigation, overflight, and other traditional uses of the sea, carefully strike this balance and generally reflect customary international law. On the other hand, exercising other navigational freedoms in the corridor of the Strait, by the United States in concert with allies and partners, might help deter conflict in and around the Strait by demonstrating resolve and enhancing naval interoperability useful in crisis or conflict.

The Strait’s Geographic Situation & Legal Status

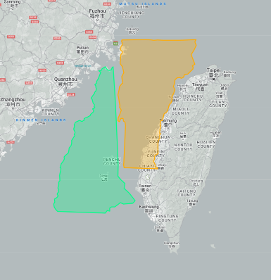

The Strait is approximately 100 miles (86 nautical miles) long and, at its narrowest point, about 100 miles (86 nautical miles) wide. To put that in perspective, both Vermont and New Hampshire could roughly fit together in the Strait.

(Source: Author created using interactive web tool The True Size.)

Of the Strait’s total width, international law only permits China and Taiwan to claim and exercise sovereignty over a narrow 12 nautical mile-wide belt of sea, known as a TTS, running along the coast of each side of the Strait (see UNCLOS, arts. 2 – 4). In other words, less than half of the Strait’s total width (the total sum of the TTS on each side) is subject to any State’s sovereignty. By contrast, more than half of the Strait’s width, the corridor, falls outside the TTS on either side of the Strait.

This is, of course, very rough math given variations in width, coastline shape, direction, maritime features, and other factors within the Strait. Moreover, both China and Taiwan measure the breadth of their 12 nautical mile TTS from straight baselines, rather than from the coastline, the latter of which is normally the proper baseline under international law (see UNCLOS, art. 5). Most, if not all, of China’s and Taiwan’s straight baselines are illegal (see here and here), and have the practical effect of pushing the outer edge of their claimed TTS further into the Strait, thereby narrowing the corridor between them. Nevertheless, even taking into account the excessive straight baselines, they still leave a relatively broad corridor beyond the resulting TTS in which high seas freedoms of navigation, overflight, and other uses related to these freedoms apply.

The key point is that a large band of the Strait falls outside China and Taiwan’s TTS even with their illegal straight baselines improperly pushing the edge of their claimed TTS farther from the coast into the Strait.

High Seas Freedoms of Navigation and Overflight Despite Overlapping EEZs & CZs

Given China’s and Taiwan’s respective CZs and EEZs overlap with the corridor laying beyond the TTS, they enjoy certain limited sovereign rights and jurisdiction related to those zones. They do not, however, have sovereignty over their respective CZs or EEZs. For example, China and Taiwan each enjoy limited jurisdiction in their respective CZs for the purpose of preventing or punishing violations of their customs, fiscal laws, immigration laws, or sanitary laws within their territory or TTS (UNCLOS, art. 33). Likewise, in their respective EEZs, their rights and jurisdiction are primarily resource-related (see UNCLOS, art. 56). Although these sovereign rights and jurisdiction in their CZs and EEZs for these limited purposes are significant, they are not the same as having sovereignty over those CZs or EEZs.

In addition, CZ and EEZ rights do not increase merely because they fall within the Strait. UNCLOS Article 35(b), for example, states that when a coastal State’s EEZ overlaps with a strait, that fact does not alter the EEZ’s legal status. As one of the world’s preeminent commentaries on the text and drafting history of UNCLOS notes, Article 35(b) confirms the treaty’s provisions on straits create “no additional rights that States bordering the strait may exercise over those maritime areas [including the EEZ] merely because they are part of a strait” (vol. II, p. 307, para. 35.7(b), emphasis added). Therefore, the mere fact that China’s and Taiwan’s EEZs entirely overlap with the corridor beyond their TTS does not confer on them any additional rights beyond those enjoyed by any coastal State in its EEZ.

As a corollary, the international community does not lose any of its navigation and overflight freedoms in the corridor simply because it overlaps with a coastal State’s CZ and EEZ. UNCLOS Article 36 provides that in straits like the Taiwan Strait, which are wider than 24 nautical miles, the freedoms of navigation and overflight guaranteed by other provisions of UNCLOS continue to apply. UNCLOS Articles 58 and 87, in turn, indicate that high seas freedoms of navigation, overflight, and other related uses apply in the EEZ beyond the TTS. The situation is different in narrower international straits (generally 24 nautical miles or less), which are not wide enough to leave a corridor of water lying between the opposing 12 nautical mile TTS. In those straits, States only enjoy more limited transit rights (see, e.g., UNCLOS, part III), such as the right of transit passage, rather than the broader range of freedoms of navigation and overflight. Broader straits, like the Taiwan Strait, are different precisely because they do leave a corridor beyond TTS.

So, while users of the corridor in the Strait beyond the TTS must have due regard for China’s and Taiwan’s respective CZ and EEZ rights in the corridor (UNCLOS, art. 58(3)), at the same time, China and Taiwan must exercise their CZ and EEZ rights with due regard for the freedoms of navigation and overflight enjoyed by all other States in that same corridor (UNCLOS, art. 52(2)).

Taiwan’s Legal Status is Immaterial to the Analysis

Some might point to the contention surrounding Taiwan’s legal status, specifically whether it is an independent State or, as China asserts, part of China and therefore subject to Chinese sovereignty. States have various national policies toward China and Taiwan on this issue. The United States’ approach, for example, is “guided by the Taiwan Relations Act, the three U.S.-China Joint Communiques, and the Six Assurances.”

This post takes no position on that issue, but whether Taiwan is an independent sovereign State or part of China is immaterial to the existence of a corridor in the Taiwan Strait that falls beyond the TTS on either side. Assuming Taiwan is part of China would not alter the legal status of the Strait’s corridor or diminish the freedoms of navigation and overflight all States enjoy in it. China cannot claim a TTS broader than 12 nautical miles or assert sovereignty over the corridor merely because Taiwan, which it claims, lies on the other side of the Strait any more than the United States can legally claim sovereignty over all the waters between the Continental United States and Hawaii.

Therefore, other States can confidently exercise their navigation and overflight freedoms in the corridor of the Taiwan Strait without (or despite) taking a position on Taiwan’s status. How a State views the sovereignty issue has no bearing on whether the corridor in which these freedoms apply continues to exist; it exists regardless.

Military Activities Are Permissible in the EEZ

Because the corridor is entirely overlapped by EEZs, it bears mentioning that a very small minority of States and legal scholars hold the view that coastal States may restrict or prohibit military activities in their EEZs (see, e.g., here). A detailed rebuttal of those views is beyond the scope of this post; suffice it to say here these views do not find support in the text or drafting history of UNCLOS’s provisions concerning the EEZ or the limited purpose of this zone. Instead, UNCLOS explicitly preserves high seas freedoms of navigation and overflight in the EEZ, as well as other lawful uses of the seas related to these freedoms. It does not exclude military vessels or aircraft from enjoying those freedoms, including military activities. The EEZ, like other ocean areas, should be used for peaceful purposes (see UNCLOS, arts. 88, 301) and with due regard for the rights of coastal States (art. 58(3)) and other users (art. 87(2)), but it is a mistake to say military activities are inherently not peaceful or without such regard. For example, naval humanitarian assistance and disaster relief exercises, or naval activities that enforce UN nuclear sanctions, are designed to promote or restore peace and stability. So, too, are other operations that help deter a conflict that threatens international or regional peace and security.

For a deeper explanation of freedom of navigation in the EEZ, see Chapter 14 of J. Ashley Roach’s seminal work on excessive maritime claims.

Exercise of Other High Seas Freedoms of Navigation in the Corridor

International law clearly guarantees, to all States, high seas freedoms of navigation and overflight in the corridor of the Taiwan Strait lying beyond the TTS notwithstanding that it overlaps with China’s and Taiwan’s CZs and EEZs. These freedoms include more than transit. Accordingly, while the recent historic Taiwan Strait transits show, importantly, that a growing part of the international community is willing to transit the Strait with naval vessels, the international community should consider exercising other navigational freedoms with their navies in the corridor. From a legal perspective, that could help protect those freedoms from encroachment and prevent mere transit from becoming a de facto ceiling for permissible military activity in the Strait, even though international law affords greater freedoms.

***

CDR Nicholas Kadlec is an active-duty Navy judge advocate and a military professor in the Stockton Center for International Law at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The views presented in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of DoD or its components.

Photo credit: 海上自衛隊, Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force