Laws of Yesterday’s Wars Symposium – Hittite Laws of War

Editor’s note: The following post highlights a chapter that appears in Samuel White’s fourth edited volume of Laws of Yesterday’s Wars published with Brill. For a general introduction to the series, see Dr Samuel White’s introductory post.

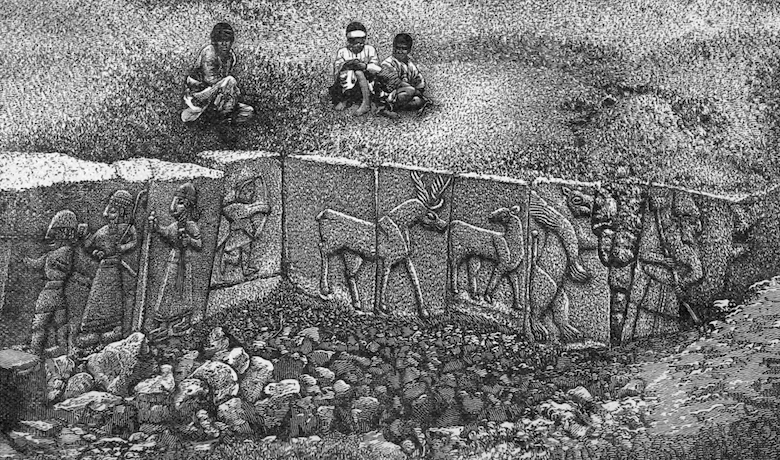

The Hittite Empire, situated in Anatolia and extending deep into the Levant, developed one of the most detailed legal and diplomatic systems of the ancient Near East. In my chapter in Volume 4 of The Laws of Yesterday’s Wars, I examine the Hittite corpus, a series of treaties, royal instructions, legal codes, and ritual texts. My examination reveals a civilisation that viewed war as a legal, moral, and religious act. Far from the image of Bronze Age warfare as unrestrained violence, the Hittites articulated clear expectations about conduct in conflict, the protection of populations, and the obligations of rulers.

Chapter Highlights

The chapter begins with a survey of Hittite political organisation. The empire relied on a network of vassal States bound by treaties that established mutual obligations, standards of behaviour, and penalties for violations. These treaties often included clauses governing the treatment of civilians, the handling of prisoners, and the responsibilities of rulers during military campaigns. I note that these documents create one of the earliest known systems of codified inter‑State norms.

A key insight lies in the Hittite fusion of religion and law. Oaths sworn before the gods gave treaties their binding force, and violations were believed to trigger divine punishment. This framework made following the rules not merely a political preference but a sacred obligation. The gods served as guarantors of good conduct, and rulers who engaged in reckless violence risked both earthly revolt and cosmic retribution.

The sources make it clear that the Hittites were concerned with the law of war concepts of proportionality and predictability. Their laws of war emphasised honourable conduct and required rulers to maintain stability in conquered territories. Prisoners were often integrated into the empire’s labour systems (some free, some enslaved) rather than executed, reflecting a strategic preference for utility over annihilation. Similarly, agricultural lands were typically preserved, as the empire’s stability depended on steady tribute and agricultural production. Warfare, in the Hittite worldview, was a legal act embedded within a broader administrative logic. Just as importantly, there was nothing in Hittite cosmology or political theology that demanded wanton destruction, in stark contrast to other ancient Near Eastern societies such as the Egyptians, Assyrians, and Israelites.

Another major contribution of the chapter is its examination of diplomatic norms. Hittite rulers engaged in extensive correspondence with other major powers like Egypt, Assyria, and Babylon. This correspondence reflects a complex international system governed by shared expectations. Treaties established the rules of alliance, extradition, protection, and succession, many of which indirectly shaped conduct during war. The famous treaty between Ramesses II and Hattušili III is often cited as an early “peace agreement,” but I argue that the treaty is merely one example found within a much older and richer tradition of Hittite diplomatic practice.

Importantly, the chapter does not idealise Hittite behaviour. The empire engaged in harsh reprisals, deportations, and coercive religious assimilation. Yet it also institutionalised checks on cruelty and emphasised the legitimacy of rule through justice and order. The coexistence of restraint and severity reflects a complex legal culture rather than a simple moral code.

So What?

The Hittites created one of the earliest durable systems of regulated warfare. Their treaties, laws, and ritual obligations demonstrate that humanitarian norms emerged independently across multiple civilisations, not as derivatives of later European thought. For modern scholars of international humanitarian law, the Hittite example highlights how legalism, diplomacy, and religious obligation can combine to produce predictable and restrained conduct. The chapter strengthens the central message of The Laws of Yesterday’s Wars: that the human impulse to regulate violence is ancient, global, and embedded in many different legal traditions.

***

Professor Rory Cox is Professor of History at the University of St Andrews and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

The views expressed are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Articles of War is a forum for professionals to share opinions and cultivate ideas. Articles of War does not screen articles to fit a particular editorial agenda, nor endorse or advocate material that is published. Authorship does not indicate affiliation with Articles of War, the Lieber Institute, or the United States Military Academy West Point.

Photo credit: Archibald Henry Sayce