Joint Operations in the Legal Environment: A Framework for Legal Competition, Expanded Maneuver, and Deterrence

This post introduces the concept of joint operations in the legal environment (OLE) and argues that the Department of Defense (DoD) should implement OLE to uphold legitimacy in strategic competition with China and Russia. OLE builds on U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s (INDOPACOM) counter-lawfare initiative, which launched in 2022 in response to China’s pervasive legal warfare or “lawfare.” Many scholars have written about China’s lawfare and its destructive impact on peace and security (see here, here, and here). Russia employs an equally pernicious model (see here and here).

As INDOPACOM’s counter-lawfare efforts mature, similar initiatives are taking shape across the joint force. Meanwhile, Congress is paying attention to the legal environment as an emerging arena for competition. Section 1284 of the draft 2025 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) tasks the DoD to submit a report on how best to support whole-of-government efforts to conduct “international legal operations” and counter “hostile international legal operations,” a term synonymous with China and Russia’s version of lawfare.

These developments presage a requirement for the DoD to institutionalize an approach to compete in the legal environment on a global scale. This post outlines a potential approach by exploring the theory and practice of OLE along with prospective applications across the joint force. For the purposes of the following discussion, OLE refers to military actions that reinforce legitimacy by focusing on actual and perceived legality in joint operations.

Operations in the Legal Environment: Theory

The viability of OLE in joint operations rests on the proposition that the legal environment is a competitive space in which expanded maneuver will contribute to deterrence. As detailed below, implementing OLE requires the joint force to: (1) compete for legitimacy; (2) expand maneuver into the legal environment; and (3) incorporate legal deterrence into its integrated campaign approach to deterrence.

Competition for Legitimacy

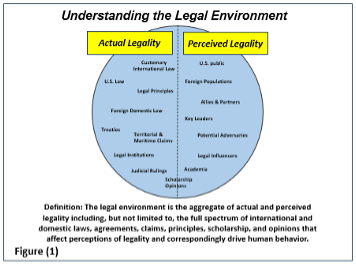

Competition in the legal environment is fundamentally a contest for legitimacy. Joint doctrine establishes legitimacy as a “decisive” principle of joint operations. Importantly, joint doctrine recognizes both actual legality and perceived legality as essential to legitimacy.

The joint force is proficient in compliance with actual legality. The DoD trains its forces to follow the law and embeds legal advisors across the joint force to ensure compliance. But legal compliance alone does not guarantee legitimacy if military actions are not perceived as lawful. In other words, perceived legality does not necessarily follow from actual legality. Nevertheless, the DoD has not adopted a methodology to specifically address perceived legality in joint operations. OLE aims to close this gap by connecting actual legality to those perceptions of legality that underlie legitimacy. Fortifying this nexus is critical to holding the mantle of legitimacy in legal-cognitive spaces under attack by China and Russia.

China’s lawfare approach codified in the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) “three warfares” strategy is useful to consider as an analog. Like OLE, China’s lawfare seeks to harness the power of perceived legality as a legitimating force, but unlike OLE, China’s lawfare lacks a tether to actual legality. Indeed, what the law is does not impact the PLA’s pursuit of so-called “legal principle superiority” as much as what target audiences perceive the law to be. This reflects a key distinction between authoritarian versions of lawfare and OLE, and more broadly between Marxist-informed perspectives on the law and Western legal tradition. It also underscores that the joint force cannot take legitimacy for granted as perceived legality is under constant threat.

Expanded Maneuver in the Legal Environment

Like other emerging domains, the legal environment is a space for expanded maneuver. The concept of expanded maneuver is a tenet of the Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC), which is the “unifying vision” for the future direction of the joint force. Some have described expanded maneuver as “fluidly moving through space and time” in all operating areas. Most important for this analysis, expanded maneuver is not limited to the domains enumerated in joint doctrine. Rather, the JWC challenges the joint force to expand maneuver into competitive spaces not traditionally regarded as domains.

Expanding maneuver into the legal environment requires the joint force to quantify and understand the legal environment as an operating area. Although joint doctrine does not define the legal environment, it is best described as the aggregate of actual and perceived legality. It includes, but is not limited to, the full spectrum of international and domestic laws, agreements, claims, principles, scholarship, and opinions that affect perceptions of legality and correspondingly drive human behavior [see Figure (1)]. The legal environment overlaps with the information environment and interacts in time and space with all other operating areas.

Expanding maneuver into the legal environment requires the joint force to quantify and understand the legal environment as an operating area. Although joint doctrine does not define the legal environment, it is best described as the aggregate of actual and perceived legality. It includes, but is not limited to, the full spectrum of international and domestic laws, agreements, claims, principles, scholarship, and opinions that affect perceptions of legality and correspondingly drive human behavior [see Figure (1)]. The legal environment overlaps with the information environment and interacts in time and space with all other operating areas.

Expanded maneuver in the legal environment involves the integrated employment of OLE to gain or maintain a legal position of advantage over an opponent. Practically, it requires orienting forces and capabilities to contest lawfare by China and Russia, identify legal threats, seize opportunities, and implement action matched with the right resources and expertise. At the same time, it exploits legal compliance as a relative strength. In other words, the joint force need not assault legal terrain from exterior lines like China and Russia, but instead can maneuver to defend and reinforce the legal high ground it already holds by virtue of adherence to the rule of law.

Legal Deterrence

OLE supports the DoD’s priority to deter aggression in accordance with the National Defense Strategy’s core concept of integrated deterrence. Denying legitimacy to potential aggressors such that the foreseeable costs of aggression outweigh the benefits is the foundation of legal deterrence in joint operations. In this sense, OLE contributes to what deterrence theorists call “deterrence by denial.” If deterrence fails, OLE prepares the battlespace by securing the legitimacy required to prevail in conflict.

INDOPACOM’s counter-lawfare efforts exemplify this approach. Blocking the PLA’s pursuit of “legal principle superiority” is the cornerstone of INDOPACOM’s theory of legal deterrence. China will be less likely to resort to aggression if denied the veneer of legitimacy intrinsic to “legal principle superiority.” Key to INDOPACOM’s approach is the understanding that China contorts the legal underpinnings of legitimacy to fit its authoritarian model. Certainly, one could say the same for Russia. China and Russia are likewise adept at leveraging incremental gains in perceived legality among select audiences in ways that subtly increase maneuver space. Over time, these incremental gains can accumulate toward broader objectives.

Legal deterrence must therefore function together with expanded maneuver to compete for legitimacy across the complex expanse of legal issues and human terrain that China and Russia seek to manipulate. Moreover, the strength of legal deterrence depends on integrating with other elements of deterrence so that China and Russia have more to lose than already-sullied reputations. To be sure, legal deterrence alone is not a panacea, but it can nonetheless be a valuable component of a broader deterrence strategy.

Operations in the Legal Environment: Practice

OLE integrates various capabilities and authorities in support of the Joint Force Commander’s (JFC) objectives. Legal expertise is critical, but OLE is not purely a legal function or the sole responsibility of the JFC’s legal advisor. Among other functional experts and interorganizational partners, the J2 (intelligence), J3 (operations), J5 (strategic plans and policy), public affairs officers, foreign policy advisors, and foreign liaison officers all play important roles. The JFC could assign an OLE program manager to coordinate OLE across joint functions and staff directorates. The five categories of OLE described below are not necessarily all-inclusive, but representative of emerging practice areas, ripe for broader application across the joint force.

Legal Vigilance

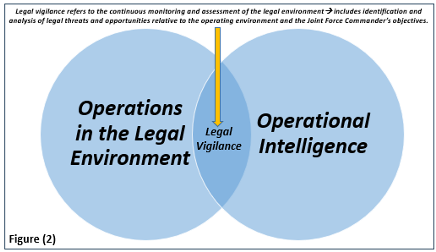

“Legal vigilance” refers to continuous monitoring and assessment of the legal environment. “Monitoring” involves the identification of legal threats and opportunities (e.g., behaviors that undermine the rule of law, legal narratives in the information environment, developments in international law, rulings by foreign courts, and new maritime or territorial claims). Monitoring informs “assessment,” which involves analysis of legal strengths, weaknesses, and centers of gravity. Relatedly, assessment should deduce those perceptions of legality that competitors seek to exploit and to what ends.

Legal vigilance is critical for detecting legal indications and warning of potential aggression. In a Taiwan crisis, for example, China might act in the legal environment as a precursor to invasion by declaring a “major incident” under Article 8 of the anti-secession law or publishing straight baselines around Taiwan under Article 16 of the Law of the Sea Convention. This example underscores the overlap between legal vigilance and operational intelligence, and the resultant necessity for collaboration between legal advisors and intelligence officers to fully inform the JFC’s estimate of the situation [see Figure (2)]. To that end, such collaboration should incorporate intelligence requirements to account for operationally significant changes in the legal environment, as well as procedures to collect, process, and analyze legal intelligence.

Legal vigilance is critical for detecting legal indications and warning of potential aggression. In a Taiwan crisis, for example, China might act in the legal environment as a precursor to invasion by declaring a “major incident” under Article 8 of the anti-secession law or publishing straight baselines around Taiwan under Article 16 of the Law of the Sea Convention. This example underscores the overlap between legal vigilance and operational intelligence, and the resultant necessity for collaboration between legal advisors and intelligence officers to fully inform the JFC’s estimate of the situation [see Figure (2)]. To that end, such collaboration should incorporate intelligence requirements to account for operationally significant changes in the legal environment, as well as procedures to collect, process, and analyze legal intelligence.

In joint planning, planners must apply legal vigilance toward understanding the legal environment in design methodology and mission analysis. This includes cognizance of the interaction between the legal environment and all other domains. When planners understand the legal environment in the context of the larger operating environment, they may then develop courses of action to create effects in the legal environment or integrate OLE options into courses of action for the JFC’s consideration.

Legal Operations in the Information Environment

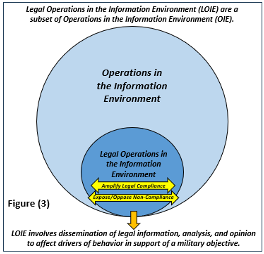

OLE practice is partly a subset of operations in the information environment (OIE). This post characterizes the overlap between OLE and OIE as legal operations in the information environment (LOIE) [see Figure (3)]. LOIE involves the integrated dissemination of legal information, analysis, and opinion to affect drivers of behavior in support of a military objective. Typically, LOIE will amplify the joint force’s compliance with the rule of law or expose and oppose the misuse of the law by a competitor. LOIE includes the release of standalone legal products, but it also encompasses the integration of legal messaging across the spectrum of information capabilities, from public affairs and military information support operations to key leader engagement and public speaking. Beyond the information environment, the JFC can integrate LOIE with operations in the physical domains or in cyberspace.

OLE practice is partly a subset of operations in the information environment (OIE). This post characterizes the overlap between OLE and OIE as legal operations in the information environment (LOIE) [see Figure (3)]. LOIE involves the integrated dissemination of legal information, analysis, and opinion to affect drivers of behavior in support of a military objective. Typically, LOIE will amplify the joint force’s compliance with the rule of law or expose and oppose the misuse of the law by a competitor. LOIE includes the release of standalone legal products, but it also encompasses the integration of legal messaging across the spectrum of information capabilities, from public affairs and military information support operations to key leader engagement and public speaking. Beyond the information environment, the JFC can integrate LOIE with operations in the physical domains or in cyberspace.

INDOPACOM’s published counter-lawfare products illustrate LOIE. For instance, INDOPACOM’s Tactical Aids (“TACAIDs”) reinforce legitimacy by informing interested audiences on legal matters impacting the JFC’s objectives. TACAIDs also supply cogent language for incorporation into other forms of strategic communication. INDOPACOM’s TACAIDs, newsletters, and multilateral information papers have circulated on social media, in news articles, and broadly with allies and partners. The reach of INDOPACOM’s counter-lawfare products proves the viability of LOIE as an emerging information capability. Replicating similar models across the joint force, however, will require institutional changes and a commitment of limited human resources, as detailed in the recommendations below.

Legal Institutional Capacity Building

Federal statutory law defines legal Institutional Capacity Building (ICB) to include defense security cooperation activities to strengthen partner nation legal frameworks in support of shared objectives. Program designers shape legal ICB to foster the legal resilience necessary to uphold the rule of law and deny competitors from exploiting legal vulnerabilities for military advantage. The Defense Institute of International Legal Studies (DIILS) is the lead defense security cooperation resource for legal ICB. DIILS routinely deploys teams of civilian experts and judge advocates to engage with allies and partners around the globe. In fiscal year 2024, DIILS reportedly executed legal ICB programs with 54 partner nation militaries.

Although the DoD is already executing legal ICB broadly, opportunities remain for the joint force to incorporate legal ICB under the umbrella of OLE for greater effect. Legal ICB can open important lines of communication for LOIE. It also builds trust, relationships, and a globally networked legal community, which enables other forms of OLE. Moreover, the JFC could charge his or her assigned OLE program manager with aligning legal ICB to the JFC’s legal and security cooperation initiatives. Doing so would involve coordinating with DIILS to tailor legal ICB programs and build legal ICB teams composed of statesmen, cultural specialists, and technical experts to meet the needs of the partner while advancing toward the JFC’s objectives.

Legal Diplomacy

Legal diplomacy involves international engagement to forge consensus on key issues and build legal strength in numbers in support of the JFC’s objectives. Unlike legal ICB, legal diplomacy may encompass engagement with potential adversaries in addition to allies and partners. Generally, involved parties center legal diplomacy engagements on a specific list of topics and desired outcomes, and produce a record. Engagements can occur in a small group setting or as part of a larger conference, exercise, or series of meetings, and may be bilateral or multilateral. All sides share respective views and work to identify opportunities for cooperation, fortify areas of agreement, and mitigate points of divergence.

The Department of State’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs executes an “intensive” legal diplomacy program. INDOPACOM’s counter-lawfare center supports Department of State led legal diplomacy engagements in alignment with the JFC’s objectives. INDOPACOM also executes its own military-legal diplomacy initiatives, including the annual International Military Law and Operations (“MILOPS”) conference and a series of trilateral legal engagements with Japanese and Australian defense counterparts. INDOPACOM often works with allies and partners to document and publicize legal diplomacy engagements, demonstrating the ability to integrate legal diplomacy and LOIE across the spectrum of OLE.

Interorganizational Legal Partnership

Interorganizational legal partnership (ILP) involves partnering with U.S. departments and agencies, state and local governments, foreign militaries, intergovernmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector to unify efforts toward shared objectives. It includes, for example, interoperability training with foreign partners and negotiation of posture agreements. It also covers partnership efforts with the Department of State and the broader interagency to eliminate legal stovepipes and combine effects. Finally, ILP may include partnerships with academia, think tanks, private law firms, and other institutions. Such partnerships could involve legal vigilance exchanges, legal information campaigns, national security litigation, or any number of other complementary efforts.

ILP collectivizes legal power to offset freedom of action enjoyed by competitors who disregard rules and norms. It is a way for the joint force and other law-abiding entities to employ “legal asymmetry” through the application of creative, collaborative, and integrated legal approaches. Implementing ILP initiatives requires OLE practitioners to cultivate networks outside of the joint force and to work with individuals and organizations that share common cause with the JFC. As an example of a best practice, INDOPACOM and the National Defense University have co-sponsored workshops with interagency and private-sector partners to foster improved collaboration on legal challenges in the Indo-Pacific.

Recommendations for the Joint Force

INDOPACOM has firmly established its counter-lawfare center. Other Combatant Commands are building similar programs. As these efforts expand, the DoD should consider implementing guidance to institutionalize concepts, best practices, and lessons learned. The following recommendations are a starting point for continued growth.

Standardize Lexicon

The joint force should standardize a common lexicon for incorporation into the DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. This includes settling on an overarching term for the activities characterized in this post as OLE. The term “OLE” is aligned to the draft NDAA and the longstanding “legal operations” program administered by NATO’s Office of Legal Affairs. It is also consistent with other doctrinal terms (e.g., OIE). OLE provides an umbrella framework to encompass, but not supplant, counter-lawfare and related initiatives.

“Counter-lawfare” may be another option if “OLE” is not acceptable. While some have embraced the term “counter-lawfare” due to INDOPACOM’s efforts, others object to the use of “lawfare” in any formulation. Lawfare tends to evoke controversy because of its long association with misuse of the law and its more recent use in U.S. political discourse (perhaps this is why Congress referred only to “legal operations” in the draft NDAA). Regardless of the terminology adopted, the act of standardization is most important. By instituting a joint lexicon, the joint force will operate from a point of shared understanding and free from semantical debates on terminology.

Incorporate OLE in Joint Doctrine

Updates to joint doctrine are necessary to promote a common perspective from which to plan, train, and conduct OLE. Specifically, OLE theory and practice warrant an annex to Joint Publication (JP) 3-84 (Legal Support), if not a standalone publication. In addition, OLE concepts merit inclusion in multiple JPs. For example: JP 2-0 (Joint Intelligence) should address legal vigilance; JP 3-04 (Information in Joint Operations) should integrate LOIE; JP 3-08 (Interorganizational Cooperation) and JP 3-20 (Security Cooperation) should cover aspects of legal ICB, legal diplomacy, and ILP; and JP 5-0 (Joint Planning) should include OLE considerations in planning. Additions to the Universal Joint Task List could follow updates to joint doctrine as a mechanism to implement OLE training requirements, collect lessons learned, and capture resourcing requirements across the joint force.

The bottom line: INDOPACOM’s work has resulted in best practices, insights, and new concepts that should be codified in support of national defense priorities. It is time for joint doctrine to catch up.

Institute OLE in Joint Plans, Policies, and Orders

OLE is suitable for inclusion in global and theater campaign plans, execution orders, and DoD issuances. As one example, the 2023 DoD Strategy for OIE invites “innovative new concepts” in a DoD OIE implementation plan and future OIE policies. OLE—or more specifically, LOIE—is the type of concept that leaders could incorporate to improve the overall effectiveness of the DoD’s efforts in the information environment. Instituting OLE in plans, policies, and orders will empower execution across the joint force while ensuring compliance with U.S. policy. Moreover, it will provide a foundation for JFCs to orient OLE capabilities and capacity toward their objectives.

Resource and Train for OLE

OLE provides low-cost opportunities for competitive advantage in a resource-constrained environment, but capitalizing on these opportunities nonetheless requires appropriate investment in joint capability and capacity. Within the legal community, the services’ Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps could support the joint force with dedicated OLE training for judge advocates ahead of assignment to joint positions and the formation of a cadre of OLE specialists with skillsets honed to match joint requirements. Beyond the JAG Corps, a culture change is necessary for the joint force to regard the legal environment not merely in terms of compliance, but also through the lens of expanded maneuver. This can be achieved in part by instituting broader exposure to OLE concepts in joint professional military education. Likewise, prospective commanders, information professionals, intelligence officers, foreign area officers, and operational planners should receive tailored instruction on OLE during service and joint training pipelines. With the right resources and training, the joint force will be better prepared to deter conflict by maintaining advantage in the legal environment.

Conclusion

Section 1284 of the draft NDAA reflects an emerging requirement for the DoD to implement OLE theory and practice across the joint force. Seizing on this requirement begins with recognition of the legal environment as an operating area in which competition for legitimacy is paramount. Maintaining legitimacy now and during future conflicts compels the joint force to expand maneuver into the legal environment and to support deterrence by denying competitors from using so-called “legal principle superiority” as an instrument of coercion or pretext for aggression.

To that end, OLE encompasses a suite of capabilities, including legal vigilance, LOIE, legal ICB, legal diplomacy, and ILP. INDOPACOM and others are leveraging these capabilities already, but integrated, force-wide application requires action by the joint force at the national level. Specifically, the joint force should: standardize OLE lexicon; revise joint doctrine to incorporate OLE concepts; update plans, policies, and orders to integrate OLE tools where appropriate; and commit to the resourcing and training required to institutionalize joint OLE capability and capacity. As China and Russia continue to actively undermine the current legal order, now is the time for the joint force to push back by implementing OLE.

***

Commander Timothy Boyle is a post-graduate student at the U.S. Naval War College and formerly the Chief of National Security Law at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

Photo credit: ISAF Headquarters Public Affairs Office