Lawfully Using Autonomous Weapon Technologies

Editor’s note: This post is derived from the author’s recently published book Lawfully Using Autonomous Weapon Technologies, published with Springer Press.

We, members of the human race in 2024, already live in a world saturated with artificial intelligence (AI). Like many technologies, we use it daily and willingly, without truly understanding how it functions. For the majority of AI-users, this is unproblematic. Much of modern technology is too complex to demand full comprehension from its users. We can live with not knowing how an engine functions as long as the car gets us to work, and we don’t need to know why Naïve Bayes was chosen as the machine learning approach for our spam filter.

But what do we expect of users if the technology in question is deadly, like commanders wielding autonomous weapons (AWS)? International humanitarian law (IHL) does not require a force to ensure that all handlers of modern armaments are degreed engineers. But it is evident that they must know enough to make the requisite legal decisions before deploying these weapons.

This, however, presents a practical challenge: the responsibilities of the military commander are many and their tasks already demanding. In addition, for weapons powered by AI, intuition is often not enough. Even without specific training, a decently-experienced commander will understand when using a rocket launcher will pose undue risk to the civilian population. But no amount of practical experience will allow a commander to understand why a reflection from a stained-glass window would suddenly make their (otherwise perfectly-reliable) AWS glitch.

To allow lawful and responsible use of AWS, we need to empower its end-users (i.e., commanders) with a method allowing them to know what elements to factor into their judgment, without this being so burdensome that it prevents them from making swift and effective decisions on the battlefield.

“Using” AWS

It is with this motivation that I wrote the book Lawfully Using Autonomous Weapon Technologies. Perhaps surprisingly, the most important word in the title is also the least conspicuous of the five: “Using.” This key word captures two core properties of the book.

First, it focuses on the level of use, i.e., the operational and tactical levels. It invites readers to think very concretely, to put themselves in the position of the figurative commander on the warfront, holding in their hand an autonomous weapon. The book is agnostic as to whether the AWS has gone through extensive review, or was hastily smuggled across the border. The AWS is simply there, in the commander’s possession, and an operation is about to commence. Should they deploy it? In what way? What relevant information should they collect, and how should they process these datapoints when making deployment decisions? Using both theoretical analysis and hypothetical targeting scenarios, these are the questions that are explored and answered in this book.

Second, it focuses on the experience of the actual end-user, the operational commander. They are the book’s main protagonist and point-of-view character. Commanders represent the key to IHL implementation, and their role is decisive. This book is demanding on its protagonist, but not unreasonable. Warfighting is difficult: time for deliberation is short, and intelligence often incomplete. Commanders cannot be expected to be AI experts. The book acknowledges these operational realities. Instead of looking for future solutions or norms de lege ferenda, it therefore explores how existing legal frameworks and military practices can be leveraged to help AWS-users make better decisions, with tools they already have.

Familiar Tools, Helpful Innovations

One example of an existing operational tool that is used is the targeting cycle, which forms the basis of the book’s overarching theory on how an AWS user can remain in control of their system. Control, I assert, is an involved and iterative process that commences long before actual deployment by analysing the technology, environment, and adversaries. It peaks in importance during the decision whether and how to use the system, and persists even after release, by assessing effects and learning from both successes and failures.

The basic framework will be easy to grasp for any commander familiar with the NATO Targeting Cycle, which also uses this integrated way of thinking in Phases 3 through 6. Following this methodology guarantees that commanders will be sufficiently cognitively involved in the decision to deploy an AWS, while also ensuring that the controls they enact to restrict the AWS’s behaviour is meaningful. The foundation is not new, but the operationalisation to AWS is.

Another example of the book using a familiar tool in a novel way is in its discussion on the desirability of using AWS. AI has many vulnerabilities and weaknesses. Commanders must not be blinded by the novelty of these weapons and must be able to discern when it is militarily or practically beneficial to simply use non-AI alternatives. To streamline this decision-making process, a risk-benefit methodology is introduced that juxtaposes the unique advantages of AI with the difficulty of actually using the system lawfully. This risk-benefit chart is inspired from existing risk assessment matrixes and collateral damage matrixes, which also require commanders to weigh expected benefit with expected risk. As with the control framework, incorporating this system into existing targeting policies should thus not present obstacles, nor would training commanders in it be difficult.

The book also features innovative theories. One example is the concept of the Intended Operational Environment (IOE), which was introduced to mitigate the AI problem of infinite variance. Data-driven AI apply a logic alien to us and utterly banal input variations (like snow or innocent-looking turtles) can entirely compromise normally well-functioning AWS. A dataset can never be truly comprehensive and it is impossible for validation and review to test for all possible inputs, leaving commanders with a practical problem: how can they ever be convinced that their AWS is (and will remain) discriminate for the planned operation?

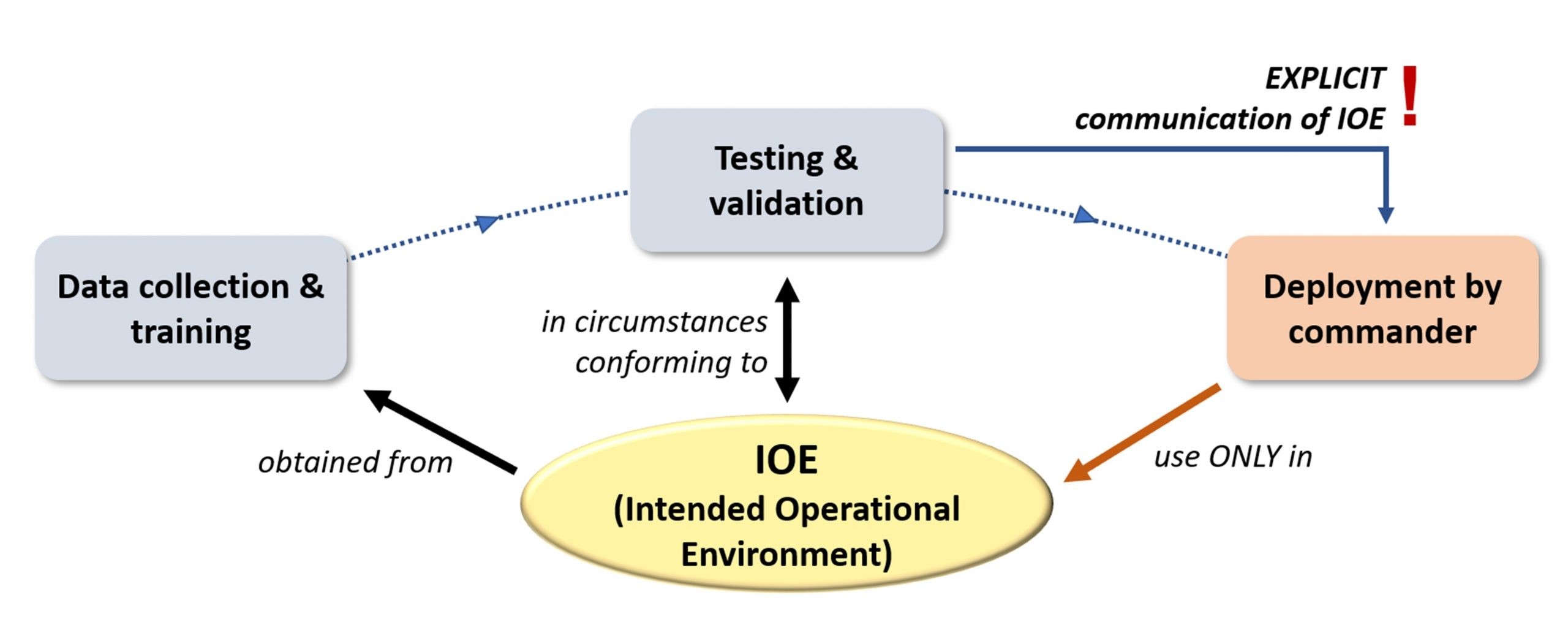

The solution proposed in this book is for programmers, reviewers, and commanders to adopt a clear IOE between them (see Fig. 1), e.g. “medium-to-low-density towns and suburbs, against regular forces, daytime, no extreme weather.” This IOE would unambiguously fix the operational context for which a particular system was designed, tested, and validated. This offers guarantees to commanders that they can rely on the legal assessment made by reviewers, as long as they do not deviate from this IOE. Ultimately, it is a practical solution to a complex technical problem.

Streamlining Decision-Making

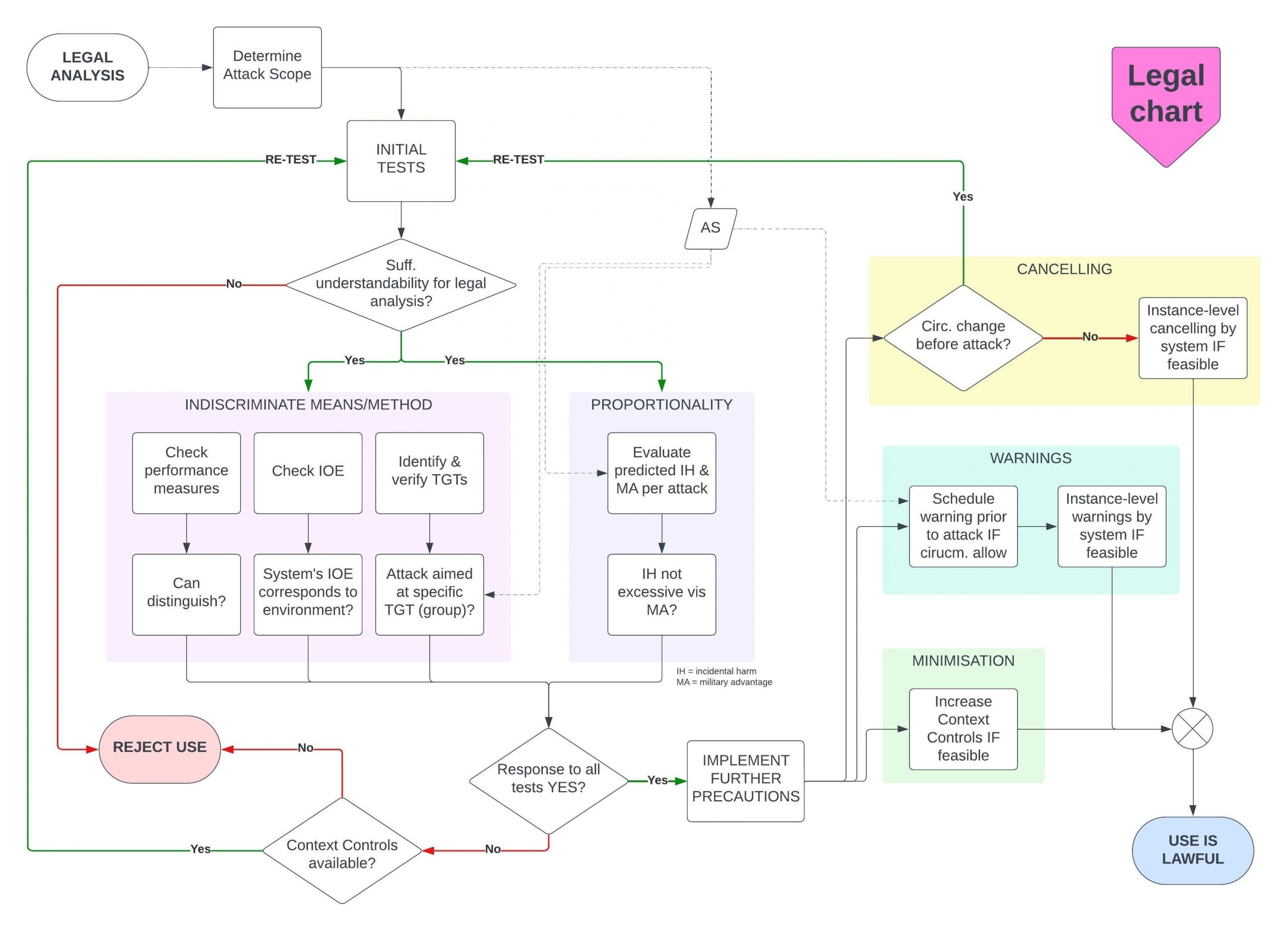

It has likely become apparent that facilitating and streamlining the commander’s decision-making process is a key theme of this book. Most of its theoretical findings are supported with practical summaries and diagrams that translate these conclusions into workable summaries, accessible to the practitioner. This is congruent with the point-of-view adopted, that of the military commander. This perspective obliges us to be sympathetic to the difficulties and pressures of operational decision-making, which will not permit commanders to extensively analyse an “eXplainable AI” solution or scrutinise half a dozen AI accuracy metrics in detail as they are pressed to plan their next attack. To enable correct legal decisions, they need a system that is concise while not being reductive.

One way the book tries to achieve this aim is through distilling its legal and theoretical findings into checklists or workflows. The concluding chapter features three flowcharts that essentially condense the entire work’s findings into a single, continuous, easy-to-apply process. For example, the second flowchart of the three (reproduced in Fig. 2) is centred around Arts. 51 and 57 of Additional Protocol I. It offers commanders and their legal advisers a systematic way to analyse, prior to ordering any AWS-attack, whether their system would be lawful to use under these targeting rules. Inefficiencies are minimised through ease of use, its structure (it quickly becomes apparent if a system is inappropriate if process arrows lead to REJECT USE), and the addition of cognitive tools such as the “Attack Scope.” It makes the book’s theoretical conclusions approachable and workable, without sacrificing precision.

Another way the book tries to ease a commander’s cognitive load is by clearly delineating which duties are incumbent upon them, and which are the responsibility of the State. A commander’s agency with respect to AWS is actually quite limited. Many legally-relevant elements (e.g., reliability and performance, understandability, review and validation, etc.) are faits accomplis. They are out of the user’s control at the deployment level. Responsible use of AWS requires cooperation and coordination between the operational and structural levels. Commanders rely on their higher-ups to provide, for example, a clear IOE, accuracy metrics, and training. Meanwhile, the State relies on commanders to use this information to make proper contextual decisions on the battlefield. To prevent role confusion, the book always clearly demarcates whether a particular legal test or measure is the responsibility of the commander or the State. This removes ambiguity and helps commanders focus on those duties which are theirs to perform.

IHL is a Collaborative Effort

In a recent discussion I participated in, the question arose how we should see the role of academics vis-à-vis that of practitioners in the overall ecosystem of IHL. My view is that the relationship is actually quite comparable to that of the State and commanders, mentioned above: they are collaborative and mutually complementing. Academics can reflect and ponder for weeks and months over minute doctrinal details. Practitioners benefit from “outsourcing” this analysis to partners who have the benefit of time, just as commanders should be able to depend on the State to conduct arduous testing and review of their capabilities before the onset of the pressures of war. Similarly, like States, academics rely on practitioners to be the guarantors of laws, to apply their findings and recommendations in practice, and to remind them of what is and is not feasible on actual battlefields.

To be fruitful, this relationship requires goodwill from both sides. On the one hand, preparedness and openness from the practitioners to listen to academic findings and recommendations. On the other, a willingness from the academics to empathise with the challenges of warfighting, and a capability to communicate ideas clearly and in an actionable manner. This author—an academic—hopes that Lawfully Using Autonomous Weapon Technologies has achieved the latter.

***

Dr Jonathan Kwik is Researcher in international law at the Asser Institute in The Hague, Netherlands.

Photo credit: Senior Airman BreeAnn Sachs