Strengthening Atrocity Cases with Digital Open Source Investigations

Editor’s note: The following post is part of the Articles of War Symposium on Beth Van Schaack’s book, Imagining Justice for Syria. The symposium offers a platform for the contributing experts to carry the conversation on justice and accountability in Syria forward.

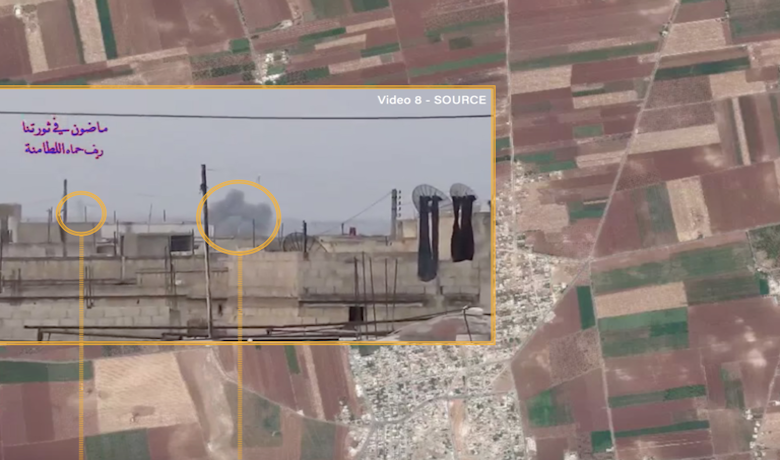

The Syrian conflict has both expanded the possibilities and tested the limits of investigating alleged war crimes with digital open source information—that is, publicly available information on the internet, such as posts to social media and other online platforms.

The massive amount of online information, its relative unreliability, and the popularity of “digital open source investigations” means that many people without extensive training or experience have suddenly jumped into the war criminal hunting game. The Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations (Berkeley Protocol) was developed in response to a real need for guidelines and professional standards on the use of online information to support justice and accountability.

Challenges

One of the most acute investigation challenges that has surfaced in the Digital Age is how to find relevant information amidst the huge quantities of content posted online. As noted in Beth Van Schaack’s new book, Imagining Justice for Syria, more hours of video footage now exist of the Syrian conflict than the actual length in hours of the conflict itself. But that’s a mere drop in the bucket compared to the total volume of online information. As of 2019, in a single minute, more than 500 hours of video were posted to YouTube, approximately 87,500 people Tweeted, and roughly 2.1 million Snaps were created on SnapChat. As Van Schaack explains, today the challenge is how to find relevant information in a cacophony of digital noise.

Another challenge is to ascertain the reliability of the content that is discovered. Issues of reliability range from staged incidents, to “deep fakes” (false content generated by algorithm), to “shallow fakes” (content that is unaltered but mischaracterized for propaganda and other purposes), to intentionally or unintentionally mislabeled information. Helpful information mingles with misinformation (the inadvertent sharing of false or mischaracterized information) and disinformation (the intentional sharing of misleading or inaccurate information), which threatens to consume investigators’ sparse resources and obscure the truth. To clarify the dangers, First Draft News has created a helpful typology of “information disorder” online, which ranges from misinformation to disinformation and malinformation (information shared with the intent to harm). The forms such information disorder take are multiple, ranging from revenge porn to propaganda to parody.

The Syrian Hero Boy Example

One video is particularly illustrative of the risks posed by unsourced content on the internet. Posted to YouTube in 2014, the video opens with a young boy lying in peach-colored dust. The camera shakes as he slowly sits then leaps to his feet and begins to run towards the right side of the viewer’s screen. There’s a sudden puff of smoke, presumably from a gun, and the boy’s knees crumple. He falls to his shins, then his stomach. Within seconds, though, he springboards up. He dashes behind a car and emerges almost immediately, pulling a young girl in pink back across the screen, their heads tucked like terrified doves as they race to safety.

When originally posted, the video languished without much attention. Three months later, when the uploaders added the title “Syrian Hero Boy,” the video went viral. Media around the world began featuring the video as an example of courage and hope emerging from an otherwise depressing and deadly war. But what quickly overshadowed the content was a heated debate: Was the video what it claimed to be? Did it depict the valiant rescue of a young girl by a young boy in the midst of gunfire in Syria?

In the case of Syrian Hero Boy, the answer turned out to be no. The now-infamous scene had been staged on the former set of the movie Gladiator by a Norwegian filmmaker. In the midst of the controversy, a BBC reporter evaluated the film and noted that her team could not tell whether or not the video was shot in Aleppo, but that it had “definitely” been taken somewhere in Syria. Even that proved wrong: the film was shot in Malta.

So how did a “low budget” film create such widespread consternation? And why did some reporters feature the video, while others did not?

One of the distinguishing factors was whether reporters used a multi-step verification process—a practice now incorporated in the Berkeley Protocol—for evaluating the authenticity of videos posted to the internet. In the case of Syrian Hero Boy, many reporters declined to show the video because of an inability to verify its source. Doubts about its provenance proved insurmountable. Many of those who showed the video, framing it as real, ignored or undervalued this step.

Digital evidence has tremendous power to shape legal narratives around the facts underlying war crimes cases. Its power is sometimes disproportionate compared with other types of evidence—such as witness testimony, which can be unreliable due to the fallibility of memory or personal and political motivations to mislead. But, despite what some may believe, videos do not speak for themselves, and legal investigators face numerous challenges in authenticating videos and images taken from the internet.

Berkeley Protocol

Compounding the two challenges mentioned above—the pervasive amount of online information and the obstacles to authenticating it—is the popularity of digital open source investigations. Many people lacking extensive training or experience are now able to “investigate” war crimes. The information ecosystem into which they’ve leapt further exacerbates the risks of unreliable work.

In response to these challenges, in December 2020, the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley School of Law and the United Nations Human Rights Office released an international protocol to disseminate guidelines and establish professional standards for the use of online information to support justice and accountability.[1] These guidelines, known as the Berkeley Protocol, address the type of problem outlined by the Syrian Hero Boy video. The Protocol is intended to increase international investigators’ ability to verify or invalidate online content. The development process, led by the coordinating committee, included consultations with more than 150 experts in technology, international law and investigations from around the world, and several workshops in which thornier legal, operational, and ethical issues were debated.

The Protocol offers methodologies that can support information identification, collection, verification, and analysis. In addition, its annexes illustrate the preparations legal investigators should take before launching a digital investigation. The latter are designed to help investigators and their teams identify the many platforms where people may post information about an incident of interest, as well as better understand any inequalities related to user-access based on gender, geography, ethnicity, and age.

Perhaps most importantly, however, the Protocol establishes a series of overarching principles for digital open source investigators to follow. In doing so, it establishes a conceptual foundation for this field of practice. Clustered into three categories—professional, methodological, and ethical—the principles are designed to help ensure those using digital open source information as potential evidence of international crimes “are accountable, competent, and that their work is carried out in accordance with the law and with due regard for security concerns … at all stages of the life cycle of their investigation.”

The professional principles relate to the investigator’s preparation to conduct digital open source investigations. They include accountability, competency, objectivity, legality, and security awareness. The methodological principles, in contrast, further safeguard the quality of the investigation, but focus more on how the work is done, than by whom. These principles include accuracy, data minimization, preservation, and security by design. Finally, the ethical principles bring important attention to who is helped and who is harmed by an investigation, and in what ways. Such ethical principles include dignity, humility, inclusivity, independence, and transparency.

Illustrative Principles in the Berkeley Protocol

While a full recitation of the principles is outside the scope of this post, a few of the principles are illustrative. The first is the principle of competency. Competency requires investigators to have appropriate training and skills to execute the activities they undertake. Given how rapidly this field of practice is evolving—with the platforms to which people publish content and the tools and methods used to access that information constantly changing—staying on top of what one needs to know is no small feat. Per the Protocol, competency does not require any particular type of accreditation, but does require that investigators stay abreast of methodological and technical developments. Moreover, it requires that investigators know when an expert should be called in to conduct advanced or specialized research.

Another noteworthy principle is objectivity. As explained in Van Schaack’s book, most investigations require fact-finders to ascertain the truth without favor to any side in a conflict. In the digital environment, this requires a heightened awareness of and strategies for countering both human and machine biases. Such biases include everything from access bias (who has access to the internet and is contributing information online, and thus which incidents and whose perspectives may be available in digital spaces), to algorithmic bias (what gets prioritized in search results, which is influenced by everything from prior search histories to geography), and cognitive biases (or “systematic errors in thinking or reasoning that impact upon human decision-making”[2]). The latter includes, for example, confirmation bias, through which investigators unintentionally overvalue information that supports their preferred working hypothesis of who did what to whom and when, and undervalue or ignore contradictory information.

Closely related to the principle of objectivity is the principle of accuracy. The principle of accuracy safeguards the quality of the investigation, and thus the growing legitimacy of digital open source investigations. Mechanisms for facilitating accuracy include generating and testing multiple working hypotheses about the facts underlying a case and engaging in peer review. The peer review mechanism is meant to check the quality of the work and to safeguard against the biases noted above. Another important mechanism is proving the null hypothesis. That is, if you believe a location featured in a video is Aleppo, can you prove that it is not? Or, can you establish enough doubt that your conclusion cannot be stated with the necessary degree of confidence?

The principle of security is overarching. For digital investigation purposes, this principle encompasses at least three conceptions of security: physical, digital, and psychosocial. Across all of these, the investigator needs to consider the safety and security of everyone who may be implicated by the investigation, as well as the integrity of the investigation itself. Affected individuals may include the investigator(s); their team; others within their organization; their family members and affiliates; the content author; the content uploader; those depicted, mentioned, or otherwise referenced in the content; and the communities of which all of these individuals are a part. Investigators located far from sites of conflict may be at relatively low risk of physical danger. For those in an affected region, however, the amplification of a video, a photograph shared online, or the publication of a report that aggregates various bits of open source data into an analytical product may dramatically increase their risk profile.

In addition to physical risks, open source investigations can trigger new digital vulnerabilities and threats. Accessing websites without masking the IP address of the connecting device or the identity of the investigator risks tipping off targets to both the investigation and the investigating team. Similarly, the vulnerability of digital communications and stored digital information to being hacked, manipulated, lost, or destroyed raises a different set of risks and threats that investigators might face when dealing with physical evidence.

Finally, the principle of security includes psychosocial vulnerabilities. Investigators and their parent organizations should pay close attention to the heightened risk of vicarious trauma and PTSD triggers that can result from working with large quantities of videos, photographs, and audio files with upsetting imagery or events. Not to be underestimated, psychological distress can have a direct bearing on physical and digital security, in addition to any mental effects on the investigators and others impacted by the investigation. Those impacted can include people from the broader public who may be affected by published findings, especially when reported in a form that suggests little sensitivity to the potential impact. Guidelines and practices to mitigate psychosocial harm need to be implemented at the individual and organizational levels.

Conclusion

Given its temporal convergence with the rise of social media and the spread of smartphones, the Syrian conflict has come to epitomize the use of digital information to document and make sense of alleged war crimes violations for advocacy and legal accountability. In doing so, it has spurred new tools and significant innovation in methods and uses along the way.

Ultimately, as Van Schaack notes, the Syrian conflict has revealed just how valuable videos, photographs, and other digital information created by those closest to sites of conflict can be for broader understanding of that conflict. This includes insight into the perpetration of war crimes and other international criminal activity. While she has also warned of the biases and weaknesses endemic to digital investigations, the entrepreneurial responses to documentation of war crimes and human rights violations—including the Berkeley Protocol—are increasingly revealing how such information may be used efficiently and effectively to strengthen accountability in courts.

***

Alexa Koenig, JD, PhD, is Executive Director of the UC Berkeley Human Rights Center, a lecturer at UC Berkeley, and co-founder of the Investigations Lab.

Lindsay Freeman, JD, Adv LLM, is Director of Law and Policy of the Technology Program at the UC Berkeley Human Rights Center.

***

Other Posts in the Symposium

- Beth Van Schaack’s Imagining Justice for Syria by Winston Williams

- Battlefield Detention, Counterterrorism, and Future Conflicts by Dan E. Stigall

- The Challenge of Intentional Attacks against Hospitals in Wartime by Bailey R. Ulbricht & Allen S. Weiner

- The Security Council Veto in Syria: Imagining a Way Out of Deadlock by Philippa Webb

- Universal Jurisdiction Investigations and Prosecutions: Syria by Alexandra Lily Kather

See also Beth Van Schaack’s book, Imagining Justice for Syria and her earlier Articles of War post with the same title.

***

Footnotes

[1] Originally published in English, the Berkeley Protocol will be available in all official United Nations languages by summer 2021.

[2] Yvonne McDermott, Alexa Koenig and Daragh Murray, “Open Source Information’s Blind Spots: Human and Machine Bias in International Criminal Investigations,” Journal of International Criminal Investigations (2021).