Ukraine Symposium – Lawful Use of Nuclear Weapons

The February invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces was followed by an even graver threat to global peace as the Kremlin announced President Vladimir Putin’s order to raise Russia’s nuclear forces into a higher state of alert. Reportedly, Putin’s order enhances his forces’ ability to transmit a nuclear launch order, making Russia less vulnerable “to decapitation in the event that either Putin or his top military advisers were dead or incapacitated.”

This was reported as the first time such an action had been taken since the Russian Federation was established in 1991, and it coincided with a thinly veiled threat of a nuclear attack, with Putin promising that any nation attempting to stop him would face consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history.” This was all done after Putin oversaw a nuclear forces exercise (including missile launches) just days prior to the invasion.

Such saber rattling by Putin may lead onlookers to wonder about the state of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. What is its purpose? Under what circumstances would it be employed and how? Would (or could) a U.S. nuclear attack comply with the law of armed conflict (LOAC)?

Overview & U.S. Policy

The U.S. nuclear force is a triad of three distinct delivery platforms (2018 Nuclear Posture Review (2018 NPR) at IX-X). The naval component consists of 14 OHIO-class submarines (SSBNs) armed with submarine-launched ballistic missiles. The OHIO-class SSBNs are scheduled to be replaced by 12 COLUMBIA-class SSBNs, designed to be operationally effective and survivable for decades to come.

The land-based component of the triad consists of 400 single-warhead Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) deployed in disbursed underground silos. This leg of the triad is also planned for modernization with the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program modernizing ICBM launch facilities and replacing the Minuteman III beginning in 2029.

The final component of the triad consists of 46 B-52H and 20 B-2A strategic bombers carrying gravity bombs and air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs). The B-21 Raider is the next-generation bomber planned to supplement and eventually replace the rest of the bomber force beginning within the next several years.

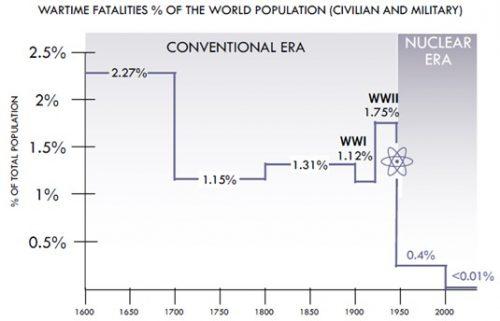

Why maintain such a lethal force? How can members of the United States Strategic Command truly believe in their motto “Peace Is Our Profession”? It may seem counterintuitive, but the deterrent effect of nuclear weapons has made the world a remarkably safer place. Through the introduction of its nuclear umbrella, the United States made essential contributions to the deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear aggression. The subsequent absence of Great Power conflict has coincided with a significant and sustained reduction in the number of lives lost to war globally, as demonstrated in the figure below (2018 NPR at 17).

This dramatic reduction in wartime fatalities is of course a credit not to the use of nuclear weapons but to their deterrent effect. Generally, deterrence “prevents adversary action through the presentation of a credible threat of unacceptable counteraction and belief that the cost of the action outweighs the perceived benefits” (Joint Publication 3-0 at VI-4).

Successful deterrence is a triad itself, requiring capability (the means to influence an adversary’s behavior), credibility (the adversary’s believability that proposed actions could actually be employed), and communication (transmitting will and capability to the adversary) (Joint Publication 3-0 at xxii). Nuclear deterrence has historically led to fewer and smaller conflicts, and discouraged the use of weapons of mass destruction, including chemical, biological, radiological, and other nuclear weapons. The United States’ historical position is that it would consider employment of nuclear weapons only “in extreme circumstances and for defensive purposes” (2018 NPR at 23).

Lawfulness of Nuclear Weapons Generally

While the United States has demonstrated its capability to use nuclear weapons and communicated its willingness to do so in certain circumstances, the question remains as to whether such communication is credible in light of the United States’s advocacy of and adherence to the rules-based international order. For the United States to credibly state that (1) it adheres to international law and (2) that it would use nuclear weapons if necessary, it follows that any use of nuclear weapons must comply with international law. Nuclear deterrence is diminished if adversaries do not believe that the United States would violate its strongly held respect for the international law in order to use nuclear weapons. Demonstrating that nuclear weapon use would comply with international law therefore increases nuclear deterrence.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) offered the most conclusive opinion on the lawfulness of nuclear weapons in a 1996 Advisory Opinion, Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons. The Court observed that the protection of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights—and in particular the prohibition against arbitrary deprivation of life—generally does not cease in times of war. However, “the test of what is an arbitrary deprivation of life [is] determined by the applicable lex specialis, namely, the law applicable in armed conflict which is designed to regulate the conduct of hostilities” (ICJ Opinion at 240).

This was precisely what the United States argued in its letter to the Court from the Acting Legal Adviser to the State Department: “various principles of the international law of armed conflict (LOAC) would apply to the use of nuclear weapons as well as to other means and methods of warfare.” On balance, the United States argued, LOAC principles do not prohibit the use of nuclear weapons generally, and any specific prohibition would depend “on the precise circumstances involved in any particular use of a nuclear weapon.”

In fact, the nuclear-weapon States appearing before the Court, including the United States, accepted that “their independence to act was indeed restricted by the principles and rules of international law” (ICJ Opinion at 239). The Court ultimately reached a number of conclusions relevant here:

There is in neither customary nor conventional international law any specific authorization of the threat or use of nuclear weapons; …

There is in neither customary nor conventional international law any comprehensive and universal prohibition of the threat or use of nuclear weapons as such; [and] …

A threat or use of nuclear weapons should also be compatible with the requirements of the international law applicable in armed conflict, particularly those of the principles and rules of international humanitarian law…. (ICJ Opinion at 266).

While some States continue to assert that nuclear weapons are illegal per se, the United States has not accepted any such treaty rule “and thus nuclear weapons are lawful weapons for the United States” (DoD Law of War Manual, § 6.18). It is the U.S. position, consistent with the 1996 ICJ advisory opinion, that LOAC governs the use of nuclear weapons just as it governs the use of conventional weapons.

In light of the conclusion that the use of nuclear weapons does not violate international law per se, we next turn to applying LOAC principles to attacks with nuclear weapons. After all, U.S. policy states that if deterrence fails, it would “minimize civilian damage to the extent possible consistent with achieving objectives,” and “the initiation and conduct of nuclear operations would adhere to the law of armed conflict” (Letter to the Court, 23). The specific LOAC principles discussed below are military necessity, humanity, distinction, and proportionality.

Military Necessity

The LOAC principle of military necessity “justifies the use of all measures needed to defeat the enemy as quickly and efficiently as possible” that are not otherwise prohibited by LOAC. Because LOAC seeks to establish general rules of broad applicability, attacking enemy combatants and military objects is generally viewed as satisfying this principle (DoD Law of War Manual, § 2.2.3.2). Military necessity also justifies incidental harm that may result from military action (consistent with the principle of proportionality, described below) (§ 2.2). Provided that attacks were made against military objectives—that is, enemy combatants or other lawful military targets—use of nuclear weapons to end a conflict and restore deterrence would generally satisfy this LOAC principle since military necessity is based on the “broader imperatives of winning the war and not only the demands of the immediate situation” (§ 2.3.3.1).

Humanity

Humanity may be defined as the principle that forbids “the infliction of suffering, injury, or destruction unnecessary to accomplish a legitimate military purpose” (DoD Law of War Manual, § 2.3). In effect, humanity is the other side of the military necessity coin—“if certain necessary actions are justified, then certain unnecessary actions are prohibited” (§ 2.3.1.1).

Prior to the ICJ’s 1996 advisory opinion, some States argued that “use of nuclear weapons would violate the prohibition on the use of weapons that are of such a nature as to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering.” In its response, however, the United States explained that the prohibition against unnecessary injury and suffering is applicable only to increased injury and suffering beyond that which is necessary to accomplish the military objective. In other words, the principle of humanity does not prohibit “weapons that may cause great injury or suffering if the use of the weapon is necessary to accomplish the military mission” (Letter to the Court, 27). For example, anti-tank munitions which must penetrate armor with increased kinetic or incendiary effects are not unlawful even though they may also cause severe and painful burns to the tank crew. The ICJ’s conclusion that there is no “universal prohibition of the threat or use of nuclear weapons” is consistent with the U.S. position on this point.

Distinction

The principle of humanity provides the foundation of the separate principle of distinction and civilian immunity from attack, since the “inoffensive and harmless character [of civilians] means that there is no military purpose served by attacking them” (DoD Law of War Manual, § 2.3.1). Under the principle of distinction, combatants may attack “enemy combatants and other military objectives,” but not the civilian population or other protected persons and objects (§5.5). Determining whether a particular target is a military objective involves a two-part test, adopted by Additional Protocol I, art. 52(2) and the DoD Law of War Manual.

First, the object must “by its nature, location, purpose or use,” make an effective contribution to military action. “Nature” refers to the type of object, especially those which are inherently military, like military aircraft, combatants, or munitions. Location refers objects and places of military value because of their geospatial significance, such as a beach that would be used as an embarkation point for an assault. “Purpose” refers to an intended or possible future use, like a bridge which provides the enemy a route of advance. “Use” refers to the object’s present function, like using an apartment building as an observation post or for military billeting (DoD Law of War Manual, § 5.6.6.1).

The “effective contribution to military action” made by a military object does not need to be direct or proximate—the contribution may be functionally remote (like a facility that manufactures items intended to be used in war materiel) or geographically remote. Similarly, a military objective is not required to provide immediate tactical or operational gains to the adversary in order to make an effective contribution.

In past conflicts, military objectives have included leadership facilities, communications objects, transportation objects, places of military significance, and economic objects associated with military operations or with war-supporting or war-sustaining industries (though such facilities may not be military objectives in all circumstances) (§ 5.6.8). War-supporting or war-sustaining industries like electric power stations and objects associated with petroleum, oil, and lubricant production generally constitute lawful objectives so long as they make an effective contribution to military action (§ 5.6.8.5).

Second, in order to be a lawful target under LOAC, a proposed military objective must be one “whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage” (§ 5.6.3). “Definite” means concrete and perceptible, “rather than one that is merely hypothetical or speculative” (§ 5.6.7.3). Targets whose destruction is intended solely to cripple civilian morale or the adversary’s economy, for example, would not result in a definite military advantage because any resulting military effect would not be concrete and perceptible.

Many objects have both a military and civilian purpose, described as “dual-use.” Airports, ships, aircraft, buildings, roads, bridges, and economic objects associated with military operations may all, depending on the circumstances, constitute objects that are usable by both military forces and the civilian population. Nonetheless, if such an object satisfies the LOAC principle of distinction, it is a military objective and may be attacked. It is still necessary, however, to consider whether such an attack would satisfy the LOAC principle of proportionality (§ 5.6.7.3).

While the United States does not adopt in either its letter to the Court or the DoD Law of War Manual a separate view of distinction for nuclear weapons, thus leaving all lawful objects as targetable subject to the other principles, some target types would be better suited for nuclear attack than others. For example, some targets, based on their size or protection measures may be better suited to a nuclear weapon than a conventional attack. In addition to legal considerations, policy and operational restraints will impact the decision to use nuclear weapons against certain targets, especially given New Start limits on the number of weapons available.

Proportionality

Proportionality is especially relevant to nuclear operations, since it refers to the principle that “even where one is justified in acting, one must not act in a way that is unreasonable or excessive” (§2.4). This LOAC principle creates an obligation for military forces

to refrain from attacks in which the expected harm incidental to such attacks would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated to be gained and to take feasible precautions in planning and conducting attacks to reduce the risk of harm to civilians and other persons and objects protected from being made the object of attack (§ 2.4.1.2).

The determination of what amount of harm is “excessive” is a difficult one, since the military commander or planners compare two different variables—“the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated to be gained” and “expected harm incidental to such attacks.” For that reason many States have declined to even use the term “proportionality,” reasoning that a precise comparison would be impossible (§2.4.1.2). Accordingly, the standard for making a determination of proportionality is due regard or diligence—not an absolute requirement to avoid incidental civilian harm completely—since such harm is “unfortunate and tragic, but inevitable” (§ 2.4.1.2). Judgments of proportionality must be made in good faith and are based on information available at the time of the decision (§ 5.3.2). What is clearly prohibited is wanton disregard for civilian casualties or harm to other protected persons.

To satisfy the LOAC requirement to take “feasible precautions,” belligerents may take actions such as an assessment of the risk to civilians, providing advance warning of an attack, adjusting the timing of an attack, or selecting appropriate weapons or aim points—all with the goal of minimizing civilian harm (§ 5.11). Commanders and planners need not account for every possible precaution, only those that are “practicable or practically possible, taking into account all circumstances ruling at the time, including humanitarian and military considerations” (§ 5.2.3.2)(emphasis added).

To demonstrate one example of feasible precautions in nuclear operations, Professors Scott D. Sagan and Allen S. Weiner have described (pp. 126 – 127) an “accuracy revolution” in missile guidance technology which allows the United States “to place nuclear and conventional warheads much closer to an intended target than was possible during the Cold War.” This accuracy revolution has occurred simultaneously with a “low-yield revolution” which has enabled the United States to develop a more flexible nuclear arsenal.

For example, the Polaris A-1 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM), deployed on U.S. submarines in 1960, had a circle error probable (CEP) of 5,900 feet and carried a 600-kiloton nuclear warhead. Half of the time, therefore, that massive thermonuclear weapon would have detonated over 1.1 miles away from the intended target, killing many civilians. The Polaris A-1 SLBM was an indiscriminate weapon. In contrast, today the United States has deployed a nuclear weapon (the B61-mod 12) with a dial-a-yield capability that reportedly can reduce the yield to 2 percent of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, generate less radioactive fallout, and has a CEP of less than 100 feet. Although a vigorous debate has emerged among scholars and in Congress about the policy implications of these technological developments, the basic facts about increased accuracy, lower yield, and reduced fallout are undisputed (Sagan and Weiner, 126-127).

While the authors of this paper do not confirm the specific facts cited in Sagan’s and Weiner’s analysis, the general ideas of increased accuracy and the ability to adjust yield reflect the United States’ commitment to proportionality and the minimization of civilian harm.

Reprisals

A final potential, but controversial, use of nuclear weapons is worth mentioning here, one that need not be entirely consistent with the LOAC principles outlined above. In certain circumstances, military forces may take actions that would otherwise be unlawful under LOAC in order to persuade an adversary to cease its ongoing violations of LOAC—such acts are known as reprisals (DoD Law of War Manual, § 18.18).

Some treaties prohibit specific means of reprisal. For example, the 1949 Geneva Convections prohibit reprisal against “wounded, sick, and shipwrecked persons” and the 1954 Hague Cultural Property Convention prohibits reprisal against cultural property (art. 4.4). But reprisals are lawful if not otherwise prohibited by treaty when certain conditions are met.

First, reprisal should follow a thorough factual investigation to confirm that the enemy has, in fact, violated the law (DoD Law of War Manual, § 18.18.2.1). Second, reprisal should only be used after other means of securing compliance have been exhausted, like protests, demands, and reasonable opportunity to cease LOAC violations prior to the reprisal (§ 18.18.2.2). Third, it is recognized that the “authority to conduct reprisal is generally held at the national level” and that individual units and military personnel are not authorized to take reprisal action (§ 18.18.2.3) (reprisal by nuclear weapons, of course, would always satisfy this criterion). Fourth, reprisal must be proportional. This is not the same as the LOAC principle of proportionality described above. The DoD Law of War Manual states that proportionality in reprisal may “not be unreasonable or excessive compared to the adversary’s violation” (§ 18.18.2.4), although elsewhere, the United States has advocated that proportionality in reprisal is what is “appropriate to bring the wrongdoing State into compliance” (para. 2.b). Finally, in order to fulfill the purpose of dissuading a State from illegal conduct, reprisals must be communicated clearly and publicly (DoD Law of War Manual § 18.18.2.5). These conditions would make preplanning reprisal targeting prior to the potential violation, especially the required legal advice, nearly impossible and require national level guidance.

Conclusion

The United States—along with 190 other States that have signed and ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty—has committed to an eventual “cessation of the manufacture of nuclear weapons, the liquidation of all their existing stockpiles, and the elimination from national arsenals of nuclear weapons and the means of their delivery” with the long-term goal of global nuclear disarmament. But as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and nuclear saber-rattling demonstrates, the global community today contains rogue actors whose aggression threatens global peace and international order. Until a time when global security conditions allow for responsible and verifiable disarmament, nuclear weapons serve as a critical deterrent to global conflict and guarantor of peace, the use of which is consistent with international law.

***

Lieutenant Colonel Jay Jackson serves as Individual Mobilization Augmentee to the Staff Judge Advocate at United States Strategic Command, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska.

Major Kenneth “Daniel” Jones is a National Security Law Attorney and Army Element Staff Judge Advocate at U.S. Strategic Command.

The views expressed here are the authors’ personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, the United States Army, the United States Military Academy, or any other department or agency of the United States Government. The analysis presented here stems from their academic research of publicly available sources, not from protected operational information.

Photo credit: U.S. Navy, Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Ronald Gutridge

RELATED POSTS

Symposium Intro: Ukraine-Russia Armed Conflict

by Sean Watts, Winston Williams, Ronald Alcala

February 28, 2022

–

Russia’s “Special Military Operation” and the (Claimed) Right of Self-Defense

February 28, 2022

–

Legal Status of Ukraine’s Resistance Forces

by Ronald Alcala and Steve Szymanski

February 28, 2022

–

Cluster Munitions and the Ukraine War

February 28, 2022

–

Neutrality in the War against Ukraine

March 1, 2022

–

The Russia-Ukraine War and the European Convention on Human Rights

March 1, 2022

–

Deefake Technology in the Age of Information Warfare

by Hitoshi Nasu

March 1, 2022

–

Ukraine and the Defender’s Obligations

by

March 2, 2022

–

Are Molotov Cocktails Lawful Weapons?

by Sean Watts

March 2, 2022

–

Application of IHL by and to Proxies: The “Republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk

by

March 3, 2022

–

Closing the Turkish Straits in Times of War

March 3, 2020

–

March 3, 2022

–

Prisoners of War in Occupied Territory

by Geoff Corn

March 3, 2022

–

Combatant Privileges and Protections

March 4, 2022

–

by Sean Watts

March 4, 2022

–

Russia’s Illegal Invasion of Ukraine & the Role of International Law

March 4, 2022

–

Russian Troops Out of Uniform and Prisoner of War Status

by

March 4, 2022

–

by

March 5, 2022

–

Providing Arms and Materiel to Ukraine: Neutrality, Co-belligerency, and the Use of Force

March 7, 2022

–

Keeping the Ukraine-Russia Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello Issues Separate

March 7, 2022

–

The Other Side of Civilian Protection: The 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention

by

March 7, 2022

–

Special Forces, Unprivileged Belligerency, and the War in the Shadows

by Ken Watkin

March 8, 2022

–

Accountability and Ukraine: Hurdles to Prosecuting War Crimes and Aggression

March 9, 2022

–

Remarks on the Law Relating to the Use of Force in the Ukraine Conflict

March 9, 2022

–

Consistency and Change in Russian Approaches to International Law

by Jeffrey Kahn

March 9, 2022

–

The Fog of War, Civilian Resistance, and the Soft Underbelly of Unprivileged Belligerency

by Gary Corn

March 10, 2022

–

Common Article 1 and the Conflict in Ukraine

March 10, 2022

–

Levée en Masse in Ukraine: Applications, Implications, and Open Questions

by David Wallace and Shane Reeves

March 11, 2022

–

The Attack at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Plant and Additional Protocol I

March 13, 2022

–

The Russia-Ukraine War and the Space Domain

by Timothy Goines, Jeffrey Biller, Jeremy Grunert

March 14, 2022

–

Fact-finding in Ukraine: Can Anything Be Learned from Yemen?

March 14, 2022

–

Status of Foreign Fighters in the Ukrainian Legion

by

March 15, 2022

–

Law Applicable to Persons Fleeing Armed Conflicts

March 15, 2022

–

March 17, 2022

–

The ICJ’s Provisional Measures Order: Unprecedented

by Ori Pomson

March 17, 2022

–

Displacement from Conflict: Old Realities, New Protections?

by Ruvi Ziegler

March 17, 2022

–

A No-Fly Zone Over Ukraine and International Law

March 18, 2022

–

Time for a New War Crimes Commission?

March 18, 2022

–

Portending Genocide in Ukraine?

by Adam Oler

March 21, 2022

–

March 21, 2022

–

Abducting Dissent: Kidnapping Public Officials in Occupied Ukraine

March 22, 2022

–

Are Thermobaric Weapons Unlawful?

March 23, 2022

–

A Ukraine No-Fly Zone: Further Thoughts on the Law and Policy

March 23, 2022

–

The War at Sea: Is There a Naval Blockade in the Sea of Azov?

by Martin Fink

March 24, 2022

–

Deportation of Ukrainian Civilians to Russia: The Legal Framework

by

March 24, 2022

–

March 28, 2022

–

Command Responsibility and the Ukraine Conflict

March 30, 2022

–

The Siren Song of Universal Jurisdiction: A Cautionary Note

bySteve Szymanski and Peter C. Combe

April 1, 2022

–

A War Crimes Primer on the Ukraine-Russia Conflict

by Sean Watts and Hitoshi Nasu

April 4, 2022

–

Russian Booby-traps and the Ukraine Conflict

by

April 5, 2022

–

The Ukraine Conflict, Smart Phones, and the LOAC of Takings

by

April 7, 2022

–

April 8, 2022

–

Weaponizing Civilians: Human Shields in Ukraine

by

April 11, 2022

–

Unprecedented Environmental Risks

by Karen Hulme

April 12, 2022

–

Maritime Exclusion Zones in Armed Conflicts

April 12, 2022

–

Ukraine’s Levée en Masse and the Obligation to Ensure Respect for LOAC

April 14, 2022

–

Cultural Property Protection in the Ukraine Conflict

by Dick Jackson

April 14, 2022

–

Results of a First Enquiry into Violations of International Humanitarian Law in Ukraine

April 14, 2022

–

Comprehensive Justice and Accountability in Ukraine

by

April 15, 2022

–

Maritime Neutrality in the Russia-Ukraine Conflict

by David Letts

April 18, 2022

–

Cyber Neutrality, Cyber Recruitment, and Cyber Assistance to Ukraine

April 19, 2022

–

Defiance of Russia’s Demand to Surrender and Combatant Status

by Chris Koschnitzky and Steve Szymanski

April 22, 2022

–

The Montreux Convention and Turkey’s Impact on Black Sea Operations

by and Russell Spivak

April 25, 2022