Laws of Yesterday’s Wars Symposium – Mongol Laws of War

Editor’s note: The following post highlights a chapter that appears in Samuel White’s third edited volume of Laws of Yesterday’s Wars published with Brill. For a general introduction to the series, see Dr Samuel White and Professor Sean Watts’s introductory post.

History is not always written by the winning side. The steppe nomads—warriors from the vast belt of open grassland stretching from the Carpathian Mountains in eastern Europe to the Pacific Ocean—are seen through the eyes of their victims. Mongol history is largely written by the settled, nomadic people they defeated, and their legacy is that of destroyers of cities; the ruiners of agriculture; the exterminators of entire people. Only dedicated academic work can allow for the reputation of the “Mongol Hordes” to be stripped back and analysed, in particular with respect to their customs and laws of war.

Mongol Culture

On this niche aspect of Mongol culture, history does not favour a positive outlook. Christopher Marlowe’s play, Tamburlaine the Great, reflects Western notions of the Mongols, through the mouth of the “Soldan of Egypt.”

Merciless villain, peasant, ignorant

Of lawful arms, of martial discipline!

Pillage and murder are his usual trades:

The slave usurps the glorious name of war

As will be seen, the Mongols were not ignorant of lawful arms or martial discipline. Quite the opposite.

Although the Mongols had confederated over a hundred years prior to Temujin—who would later go on to become Genghis Khan—the Mongghols (from which Mongol derives) were not a linguistic or ethnological group but simply the dominant tribe of one tribal confederation that inhabited the steppe north and south of the Gobi Desert. The Secret History of the Mongols (The Secret History) speaks of people with “nine tongues,” presumably dialects and languages.

Amongst this confederation were the Tatar (Tartar in English), the Naiman, the Kereyid, Uriats, Merkits, and Jalair. All were in constant competition over a finite, and seasonally varied, grassland for their horses. There was no concept of peace or war but a constantly evolving mosaic of personal and family ties which supported ever-shifting goals and desires. Equally, the distinction between soldier and herdsman did not exist—war and raiding (and the vengeance (os)) that justified them—were to the glory of the tribe and the nation. This post, whilst using the concept of “laws of war,” is necessarily focused upon the customs of battle and prohibited conduct in battle.

The Secret History is a logical source to use. Written after the death of Ogedi, but prior to the appointment of the next Khan, it describes the life of a hero but with personal details less flattering to its subject: Temujin who murders his half-brother Bekter; or Ogedi’s deathbed confession of his four failings as a Khan. It is a story of the noble class concerned with who fought, who won, and what conflicts arose amongst the Mongols themselves; sequences of actual campaigns are wrong or greatly abbreviated. It can only be relied upon, however, to a limited extent. This is because The Secret History does not reflect customary practices that were commonplace to the audience. It is, moreover, as John Man notes,

an intriguing and frustrating creation. Because it claims to explain Mongol origins, it invites comparison with other great foundational works – the Bible, the Iliad, the Norse sagas, the Mahabharata. But it lacks their scale . . . and lacks both epic grandeur and historical rigour.

Yet it captures a moment in Mongol history inaccessible through other sources, prior to generational exaggeration through the mode of an epic, and can be used to show some customs of battle that applied.

Mongol Society

To understand the two central pillars of Mongol laws of war—”the great principle” (yeke) and protecting religious buildings—it is necessary to canvass some key social rules.

Religion was of utmost importance to the Mongols, and to Genghis Khan in particular. Tengri (Tenggeri, Tngr) was the universal victory-granting sky god who migrated with the Aryans, who also held cultural taboos of exposure of the dead. Success in battle demonstrated favour from Tengri, and success was denoted by the generation of wealth. The role of the Khan then was to obtain and distribute wealth, the ultimate aim of the tribe. After a battle, supporters of rival candidates, being proclaimed rebels by the khuriltai (executive body) would be legitimately despoiled and their possessions distributed.

What was wealth to the Mongols? When appointing Temujin to be Genghis Khan, his nobles pledge,

We’ll search through the spoils

For beautiful women and virgins

For the great palace tents

For the young virgins and loveliest women,

For the finest geldings and mares

We will gather all these and bring them to you.

Maximising wealth therefore required maximising fear and so the Mongol reputation for brutality arose. This is in part propaganda spread by the Mongols and in part truth. Brutal tactics were ultimately used against mo balya, bad cities which resisted. One credible eyewitness to these tactics was Roger of Torre Maggiore, who survived as a hostage until the sudden withdrawal of Mongols in 1242.

Soon rumour spread that the Tartars had occupied the German village of Thomasbrucke where they slaughtered everyone not fit for slavery. Hearing such news my hair stood on end with fright, my whole body started trembling and my tongue refused its duty because of the unavoidable and terrible death which awaited me. In my mind’s eye I saw the slaughterers and the cold sweat of death made the blood freeze in my veins. I saw people in fear of death, unable to control their hands and weapons, unable to raise their arms or legs only staring into space. And what more? I laid my eyes on people half-dead from panic.

Others corroborated Roger’s testimony and is there is nothing to discredit the details of which he was an eyewitness. Particularly difficult campaigns would result in increasingly brutal strategies, all in the aim of minimising Mongol casualties and maximising profit.

Mongol Law

After Mongol confederation, the legal landscape changed even if the fundamental concept of wealth generation did not. The appointment of Genghis Khan saw a consolidation of multiple family groups into formal bodies of public and military order. So too did the legal landscape change, away from customary, oral history to written, codified laws.

A new series of laws aided this development, recorded as the Yassa (jasagh, yasa, yassaq). The Yassa regulated combat, inheritance, and overall public law. The Yassa had three aims: to create a legal duty and enforcement mechanism to demand obedience to Genghis Khan; to bind together nomad clans and wider members of the Empire; and the creation of a criminal code. The Yassa was particularly novel in assuring Mongols that dying without an heir did not result in property going to the Khan, which had been previous practice. Wealth generation was now intergenerational, and secured by law. There was incentive for the confederation to remain together.

Scholars of the 20th century have two different views of the Yassa: some consider it to be a codification of the ancient Turkic and Mongol legal systems, whereas others theorise that it was new imperial legislation. However, there is agreement amongst them that the Yassa was a codified legal act. The Yassa seems to have been focused purely upon Mongols, rather than their subjects, on the maxim that “People conquered on different sides of the lake should be ruled by different sides of the lake.”

No full copy survives, with only fragments of laws and ordinances having been preserved. In addition to the Yassa, the Khan made suggestions or comments—known as Bilik (knowledge)—on different occasions. Significant work by George Verndasky has collated both the Yassa and Bilik. For the purposes of this post, some rules are particularly relevant:

Rule 1 – It is ordered to believe that there is only one God, creator of heaven and earth, who alone gives life and death, riches and poverty as pleases Him—and who has over everything an absolute power.

Rule 5 – It is forbidden to ever make peace with a monarch, a prince or a people who have not submitted.

Rule 8 – It is forbidden, under the death penalty, to pillage the enemy before the general commanding gives permission; but after this permission is given the soldier must have the same opportunity as the officer, and must be allowed to keep what he has carried off, provided he has paid his share to the receiver for the emperor.

Prohibited Conduct

The Mongol Empire, by its self-interpretation, was a World-Empire-in-the-Making. Territories, rules, and people could be de facto beyond control, but de jure members of the Empire. There was therefore no concept of peace or war; but only of submission or rebellion. There therefore can technically be no concept of war crimes, as all operations (legally speaking) were domestic law enforcement or punitive expeditions. Enemies were “rebels” because of the universal declaration of Mongol jurisdiction.

The Great Principle

The Yassa required a proper declaration of war with the promise to spare the enemy population in case of voluntary submission. Mongke, the new Khan after Guyuk, held a quriltay (or gathering of leaders) in 1251. He instructed his younger brother Hulegu to the chaotic province of Iran, instructing him to,

Establish the usages, customs and laws of Genghiz Khan from the banks of the Amu Darya river to the ends of the lands of Egypt. Treat with kindness and good will every man who submits and is obedient to your orders. Whoever resists you, plunge him into humiliation.

The edicts created a legal framework for declaring mo balya. These cities breached the great principle, which was concerned with maintaining one’s word. As Genghis, after his appointment, noted,

If you change at noon what you said in the morning,

If you change the next morning what you said at midday

Such a man’s word won’t be believed.

I’ve already given you my word.

All right.

Let it stay that way.

The great principle is found throughout The Secret History. The opening scene of The Secret History shows Ambaghai Khan poisoned by the Tatars whilst enjoying their hospitality. On his deathbed, he commands his sons to not,

forget that I was betrayed by the Tatar,

You must try to avenge me with all the strength you can find,

Till the ails of your fingers wear off,

Till your fingers themselves wear away from your hands!

The Secret History informs us multiple times that the great principle is to be enforced, regardless of personal friendships or shared history. It was fundamental to the operations undertaken by the Mongols against the Tatars by Genghis. Before the battle with the four Tatar clans, the Khan,

spoke with his soldiers and set down these rules

“if we overcome their solders, no one will stop to gather their spolits.

When they’re beaten and the fighting is over,

Then there will be time for that.

We’ll divide their possessions equally amongst us.”

The battle is successful, and Genghis Khan holds a council to decide the fate of the Tatars. It is recited,

Since the old days,

The Tatars have fought our fathers and grandfathers.

Now to get out revenge for all the defeats,

To get satisfaction for their deaths,

We will kill every Tatar man taller than the linchpin on the wheel of a cart.

We’ll kill them until they’re destroyed as a tribe.

The rest we will make into slaves and disperse them among us.

Here we find an implied rule of distinction. Those that are smaller than the linchpin on the wheel of a cart (and therefore a protected category of person) and those that are not.

Protection of Places of Worship

The second pillar of Mongol laws of war related to the extreme religious tolerance across the Empire. Noting Mongolia’s geographic location as a crossroads of faith, it is unsurprising but still merits exploration.

Tengri was based upon a shamanistic approach to religion, but other models existed and were tolerated including Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism and Islam. All were preached across the steppe. As the Mongols expanded, so too did their understanding of Tengri: Tengri as manifested in Allah; Tengri as Deus; Tengri as Enlightenment.

This was both a matter of religious tolerance and religious indifference. The Secret History makes no comment as to foreign religions. Exemptions in the form of tarkan jarlips (tax exemptions) for religious sects only occur after the Empire was built. As Genghis sought to conscript able-bodied men in 1219 (in preparation for his campaign against Khwarezm) Buddhists were exempted so they would not breach their custom on killing. So too were Muslims allowed to practice with tax exemptions. In Hulgeu’s Syrian campaign, Christians were spared and Christian buildings protected. Indeed, the burning down of the Great Mosque in Aleppo appears to have been against orders and was committed by auxiliary troops (Armenian Christians to be precise).

However, Mongols enforced Shamanistic taboos across the Empire. As foreshadowed, they strictly enforced Aryan taboos on blood and exposed bodies. This manifested in two ways. First, royal blood was not to be shed. A clear example is how Prince Mstislav Romanovich of Kiev and others were bound, placed on flat ground where they became the foundation for a heavy wooden platform on which Mongol generals feasted whilst they suffocated slowly beneath them. So too Jamugha insisted that,

When you have me killed, my anda,

See it is done without shedding my blood,

And my bones are buried high on a cliff.

The taboo manifested in particular practices of Christians to worship the body parts of saints. Fighting in the Levant, Carl writes that Christian priests “paraded the bones of their saints before the Mongol army.” Accordingly, “Mongols retaliated by killing the clerics and burning their churches, priests and relics to purify themselves.” Notwithstanding, there was some level of religious tolerance and protections of places of worship, even within mo balya.

Conclusion

J.J. Saunders was wrong to suggest the Mongols wreaked havoc “out of some blind unreasoning fear and hatred of urban civilisation.” As this post has outlined, the Empire-in-the-Making took every step to maximise wealth generation and minimise Mongol casualties. Urban civilisations offered a wide spectrum of wealth; but equally they offered a lot of “useless” people. The logical strategic option, through the cultural lens of steppe nomads, was the use of these individuals as slave labour; siege warfare fodder; or artisans. When no longer useful, they were executed.

This violence was mitigated through “the great principle.” It was both a pillar to Mongol society and an approach to warfare that evolved to stop the cycle of competition and conflict between the tribes. It was a custom of warfare that was honoured above all else and enforced vigorously, and runs contrary to Marlowe’s description of a Mongol leader.

Merciless villain, peasant, ignorant

Of lawful arms, of martial discipline!

Pillage and murder are his usual trades:

The slave usurps the glorious name of war.

If warfare is the continuation of politics by other means, then it is clear the Mongols in a generation were able to rapidly focus and control their politics to generate wealth in the most effective means possible.

***

Samuel C. Duckett White is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Adelaide; as well as an Adjunct Associate Professor at the University of New England and Visiting Fellow at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

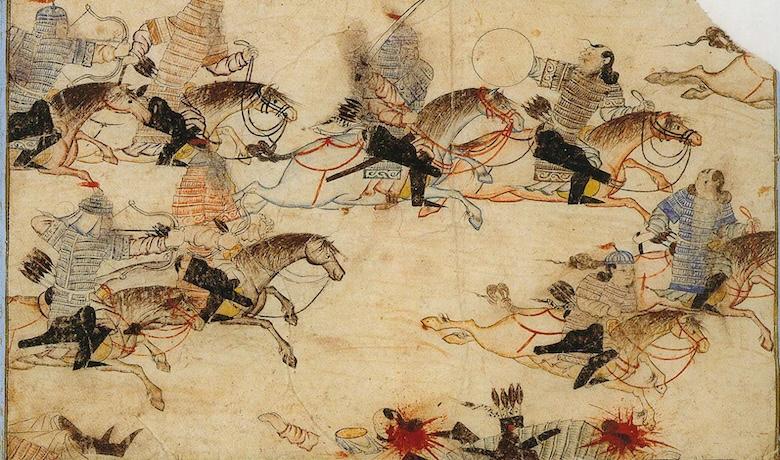

Photo credit: Staatsbibliothek Berlin/Schacht

RELATED POSTS

July 15, 2024

–

by Shadeen Ali

July 16, 2024

–

Kalaripayattu to IHL: The Ancient Roots of Legal Warfare Practices in Malabar

by

July 19, 2024

–

Rules and the “Right” in Iban Laws of War

July 30, 2024

–

by Marco Chol Ayat, Ruben SP Valfredo, Justin Monyping Ater

August 5, 2024