Israel – Hamas 2023 Symposium – Attacks and Misuse of Ambulances during Armed Conflict

The current conflict in Gaza and Israel has caused unfathomable suffering to both sides with no end in sight. The scale of deaths and destruction in such a dense civilian population and the consequences for those most vulnerable has created a humanitarian catastrophe. The daily death toll is reducing people’s lives and loved ones to numbers, pierced with personal stories of suffering.

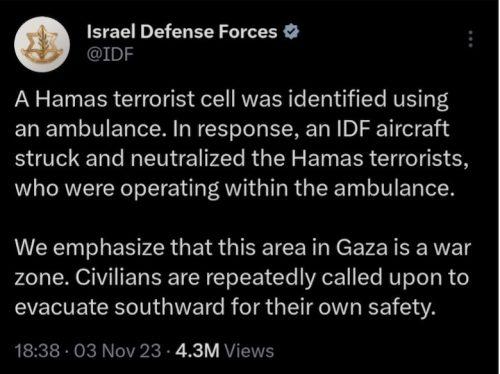

Amid this continual tide of violence, the recent attacks on hospital and ambulances mark a particularly appalling issue, given the deadly and dismembering consequences for those caught up in a place of sanctuary and aid. On November 3, an IDF airstrike hit an ambulance convoy in Gaza near the Al-Shifa hospital, killing 15 people and injuring over 60 others. Subsequently, the IDF issued the following tweet,

Ambulances have often been attacked during conflicts including in Myanmar, Ukraine, Cameroon, Syria, including a Turkish attack in a Kurdish area in 2019. From 2016 to 2017 alone, 243 ambulances were attacked in Syria with the Syrian government responsible for 123 and Russian forces damaging or destroying 60 others.

These were not the first ambulances or paramedics to be attacked in Gaza, with Amnesty International noting a number of deaths in 2009 and 2014. Such attacks against ambulances are not limited to State forces. Schmeitz et al. note that since the 1970s there have been hundreds of attacks by terrorist groups and a significant increase in the past two decades against emergency services. This post outlines the international humanitarian law (IHL) position of attacks against ambulances and how they are characterised under international criminal law, before finally addressing the issue of fighters’ misuse of ambulances as perfidy.

The Position under International Humanitarian Law

Ambulances are not ordinary civilian objects under IHL. As medical transports, they are specifically included as protected objects not to be attacked during international armed conflict, under Article 35 of Geneva Convention I (GC I) and Article 21 of Geneva Convention IV, including civilian and military organised units on land, air, or sea under Article 12 of Additional Protocol I (AP I).

For non-international armed conflicts the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) points to the broader protection under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions on the requirements concerning the collection and care of the wounded and sick, as a “subsidiary form of protection” in order to ensure that they receive medical care. Additional Protocol II (AP II), which applies to non-international armed conflicts where organised armed groups control territory, has a similar rule to the Geneva Conventions (art.11(1)).

Medical units and vehicles present a higher threshold for justifying their attack under IHL. It is not simply an issue of distinction, in that only combatants/fighters or military objectives can be attacked and the issue of proportionality weighed. Their protection can only be lost under particular circumstances and not on the basis of the units and vehicles alone becoming a military objective, as with other civilian objects. Under Article 21 of (GC I), Article 13(1) of AP I and Article 11 of AP II, medical units and transports can forfeit or loss their protection where,

they are used to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to the enemy. Protection may, however, cease only after a due warning has been given, naming, in all appropriate cases, a reasonable time limit and after such warning has remained unheeded.

Such loss of protection is an “exception” involving three elements where the medical transport is: used to commit acts harmful to the enemy; due warning is given; and there is a reasonable time for the warning to be heeded. With the first of these, acts harmful to the enemy can, according to the ICRC, include “transport of healthy troops, arms or munitions, as well as the collection or transmission of military intelligence.”

In the case of the Al-Shifa strike, the IDF further stated that the ambulance,

was identified by forces as being used by a Hamas terrorist cell in close proximity to their position in the battle zone . . . . We have information which demonstrates Hamas’s method of operation is to transfer terror operatives and weapons in ambulances.

The allegations of the ambulance(s) being used by Hamas in such a way could be characterised as acts harmful to the enemy that goes well beyond any humanitarian duties. However, the other two elements must also be satisfied. To fulfil the second element, a due warning must be given to stop misusing a medical transport for it to be targeted as a military objective. Such a warning can only be given after it has become apparent that the medical transport is being misused. A due warning can include an order to cease within a specific time period, an email address to the enemy authority in charge, a radio message, or press release (ICRC, 2016 Commentary, para. 1850).

For the final element, the time limit given to respond to a warning must be “reasonable.” This depends on the circumstances and is not a fixed limit. The 2016 ICRC Commentary to the First Geneva Convention states that on the loss of protection, the decision not to give a warning must “be taken with extreme caution” given the loss of life or further serious injury to the wounded and sick. Accordingly, such a decision is “exceptional” involving “the extreme circumstances of an immediate threat to the lives of advancing combatants, where it is clear that a warning would not be complied with” (ICRC, 2016 Commentary, para. 1849). Such a warning can be momentary.

The ICRC Commentary gives an example where soldiers advancing on a hospital come under “heavy fire from every window.” The ICRC estimates they could issue a warning and return fire without delay, as such an “imminent and severe threat” emanates from a medical object that it is clearly committing an act harmful to the enemy outside of its humanitarian duties (ICRC, 2016 Commentary, para. 1851). Meanwhile, the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s School Law of Armed Conflict Deskbook indicates there is no duty to warn in returning fire in self-defence, citing the example of the airstrikes against the Richmond Hills Hospital in Grenada, where 17 patients died after U.S. forces came under fire from the Grenadian revolutionary forces (p. 146).

In the case of the ambulance convoy outside the Al-Shifa hospital, it is unclear what, if any, warning was given. One IDF spokesperson said that established practice of Hamas since 2014 has been to use ambulance as their own “taxis on the battlefield” and a warning was given at that time. Such a warning would only effective for the specific incidents it addressed if it was given in 2014. It cannot have been effective for nearly a decade.

There have also been allegations that Hamas tried to evacuate fighters through the Rafah crossing in ambulances in the past few days. However, attacking suspected ambulances because Hamas fighters were trying to cross the border is not by itself a sufficient justification for targeting the ambulances near Al-Shifa hospital. There are temporal and spatial differences that require more caution in carrying out airstrikes to be compliant with IHL. It is unclear at this stage that the “exception” of attacking medical transports in this case has been met. This brings in the issue of whether these actions amount to a war crime.

Attacks against Ambulances as a War Crime

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) includes the war crime of intentionally directing attacks against medical units and transport (arts. 8(2)(b)(xxiv), 8(2)(e)(ii)) for both international and non-international armed conflicts). There have been no such crimes charged at the ICC, but there have been some domestic cases.

Antonio Cassese noted a case before the Italian courts in 2007, which involved Italian troops stationed in Iraq in 2004 opening fire on an ambulance. In the circumstances, the Italian troops were fighting an insurgent group in Nasiriyah. The two soldiers before the court were responsible for guarding a bridge, which the ambulance tried to cross. Per their rules of engagement, the soldiers gave warnings, flashed lights then fired warning shots at the oncoming ambulance, at which point three occupants jumped out. The soldiers continued to fire and an oxygen tank in the ambulance was hit, causing an explosion that burnt alive the remaining four occupants including a pregnant woman, her mother and brother as well as a friend.

The Court found the two soldiers not guilty of murder on the grounds of special military necessity. In the circumstances of the ongoing hostilities, the vehicle continuing to move towards their checkpoint after warnings were given posed a threat, and the soldiers complied with their rules of engagement. Cassese compared this to self-defence under international criminal law, where the question of averting immediate danger to their own lives or the lives of others and the question of the reasonableness of the continued firing on a clearly marked ambulance causing it to explode could be brought into question.

In relation to the ambulances attacked outside of the Al-Shifa hospital the question will turn on whether targeting the ambulance was reasonable and proportionate in the circumstances. Although it seems that a precise weapon was used (possibly a spike missile), the choice of means does not justify the intentional targeting of a medical transport. From the facts currently available it seems there was no immediate threat that members of Hamas were in the ambulance and about to carry out an attack, or the ambulance was being used to transport weapons.

Perfidy and Ambulances

If Hamas misused the ambulances that Israel targeted in this attack, depending on how the conflict is characterised, the persons responsible could be charged with perfidy or killing or wounding treacherously under Article 8(2)(e)(ix) of the Rome Statute or the separate offense of making improper use of the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions (art. 8(2)(b)(vii)). The ICC Elements of Crime indicate that with the war crime of killing or wounding treacherously involves the elements of perfidy, in that the “perpetrator invited the confidence or belief of one or more persons that they were entitled to, or were obliged to accord, protection” under IHL and intended to betray that confidence or belief. Misusing an ambulance as a protective medical transport to carry out attacks would satisfy this crime. The second war crime involves the distinctive emblems being used for combatant purposes directly related to hostilities in a way that is prohibited under IHL that resulted in death or serious personal injury during an armed conflict. Only using an ambulance to carry out an attack that resulted in injury or death would satisfy this crime. Proving the war crime of perfidy would require showing how the transport of weapons or Hamas fighters in an ambulance led to the injury or death of IDF or civilians.

Ambulances have regularly been used by armed groups to carry out attacks and transport weapons. In 2011, in Iraq, insurgents used ambulances packed with explosives to attack police buildings. In 2016, ISIS used two ambulances in a coordinated suicide attack in Samarra and Tikrit that killed over 25 people. The ICC has recent experience investigating perfidy and treacherty. As part of its preliminary examination into Afghanistan the Prosecutor of the ICC concluded that the Taliban has potentially committed the war crime of killing or wounding treacherously a combatant adversary (art. 8(2)(e)(ix)), citing the example in 2011 of the Taliban using an ambulance to carry out a suicide attack on the Afghan National Police training centre in Kandahar that killed 12 officers and injured others (para. 156). Similarly in 2018, the Taliban drove another ambulance laden with explosives into the government and business district of Kabul detonating it and killing over 100 people and injuring over 235 others. The ICRC has noted that the misuse of ambulances by fighters, “gravely compromises the neutrality of health-care providers,” an abuse of trust, that has “serious consequences in terms of public perceptions, effectiveness and security.”

Concluding Thoughts

The purpose of this blog is not to point fingers, but to shed light on the place of IHL in legal analysis of the use of lethal force in the Gaza/Israel conflict. The protection of medical units and transports is a primary concern of the First Geneva Convention. More generally, it fundamentally underpins the work of the ICRC and other humanitarian organizations in alleviating suffering in war.

We must articulate IHL, including its rules for targeting medical transports, in a manner that it is not simply a means to green light military operations no matter their human cost. IHL is a legal minimum, where we strive for the lowest common denominator of compliance. It is to be, as far as possible, a mitigating force on the harmful effects on war. This requires looking beyond the law, in social, diplomatic, and political forums to push for better protection for those vulnerable in conflict. This imperative is particularly acute with respect to using lethal force against medical units and transports like ambulances, where getting things wrong causes unnecessary suffering to those who are the most vulnerable in conflict.

***

Luke Moffett is Professor of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law at Queen’s University Belfast.

Photo credit: Boris Niehaus

RELATED POSTS

The Legal Context of Operations Al-Aqsa Flood and Swords of Iron

October 10, 2023

–

Hostage-Taking and the Law of Armed Conflict

by John C. Tramazzo, Kevin S. Coble, Michael N. Schmitt

October 12, 2023

–

Siege Law and Military Necessity

by Geoff Corn, Sean Watts

October 13, 2023

–

The Evacuation of Northern Gaza: Practical and Legal Aspects

October 15, 2023

–

A “Complete Siege” of Gaza in Accordance with International Humanitarian Law

October 16, 2023

–

The ICRC’s Statement on the Israel-Hamas Hostilities and Violence: Discerning the Legal Intricacies

by Ori Pomson

October 16, 2023

–

Beyond the Pale: IHRL and the Hamas Attack on Israel

by Yuval Shany, Amichai Cohen, Tamar Hostovsky Brandes

October 17, 2023

–

Strategy and Self-Defence: Israel and its War with Iran

by Ken Watkin

October 18, 2023

–

The Circle of Suffering and the Role of IHL

by Helen Durham, Ben Saul

October 19, 2023

–

Facts Matter: Assessing the Al-Ahli Hospital Incident

by Aurel Sari

October 19, 2023

–

Iran’s Responsibility for the Attack on Israel

October 20, 2023

–

by John Merriam

October 20, 2023

–

A Moment of Truth: International Humanitarian Law and the Gaza War

October 23, 2023

–

White Phosphorus and International Law

by Kevin S. Coble, John C. Tramazzo

October 25, 2023

–

After the Battlefield: Transnational Criminal Law, Hamas, and Seeking Justice – Part I

October 26, 2023

–

The IDF, Hamas, and the Duty to Warn

October 27, 2023

–

After the Battlefield: Transnational Criminal Law, Hamas, and Seeking Justice – Part II

October 30, 2023

–

Assessing the Conduct of Hostilities in Gaza – Difficulties and Possible Solutions

October 30, 2023

–

Participation in Hostilities during Belligerent Occupation

November 3, 2023

–

What is and is not Human Shielding?

November 3, 2023

–

The Obligation to Allow and Facilitate Humanitarian Relief

by Ori Pomson

November 7, 2023